The moment we need to meet

An interview with Yvette Borja of Red De DefensAZ on the struggles of immigration detainees, the power they bring to the fight, and what citizens can do to show up in solidarity.

An interview with Yvette Borja of Red De DefensAZ on the struggles of immigration detainees, the power they bring to the fight, and what citizens can do to show up in solidarity.

To make a true general strike successful, we must be able to take care of each other in the absence of powerful systems.

An interview with Ronnie Wollenzier about Tucson art-punk-bike collective BICAS, and the liberatory power of traveling on two wheels.

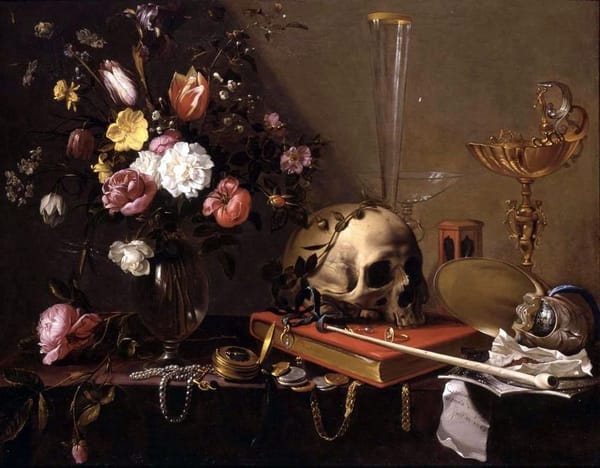

The first chapter of a book I wrote about climate change and life during end times.

Ari Aster's near-masterpiece generates all the horrors of 2020, but the big bad is a bloodsucking data center in the desert.

A conversation with Liz Casey of Community Care Tucson on the power of mutual aid, the cruelty of immigration detention, and how city officials are failing us.

Another gritty reboot

Catching up after a big move—and an exciting announcement. My fam, my goodness it has been so long I have really missed each and every one of you and hope you are all holding on tight and finding your peace and joy wherever you can.

On the brink of a big change, learning from the mesquite tree This is going to be the last newsletter before a bit of a hiatus, don't worry nothing is wrong but I do have news which is that I am moving to Tucson, Arizona. I know, big

Plastic waste is inescapable, driven by industry, and inseparable from the climate crisis Today we are going to talk about something that is very close to my heart, which is plastic, and by that I mean it is literally close to my heart because the sweatshirt I am wearing is

Today is an exciting day because we are going to talk about Children of Men, one of my favorite movies of all time.

Mark Fisher's Capitalist Realism is a grim thesis, but a tough one to argue with right now And we are back. I have missed you all I hope everyone had a decent if not great holiday and got to spend some time with loved ones and look at

A bunch of things I loved in 2021 I've been working on some year-end retrospective things for work lately and maybe it's just the contrast to how darkly dramatic 2020 and especially its conclusion were, but I've been having a hard time sort of

The third annual Crisis Palace feel good guide to year end giving One of the things about living during the Biden administration is that the Republican Party's horrors hit differently than they did under Trump, when they were mostly inescapable, because try as you might, you could not

Featured

In Wendy Brown's Undoing the Demos, neoliberalism brings the tyranny of the market and the death of the democratic project -- Oh boy, another issue being written right as our Diarrhea Country kicks into full gear, in this case the Kyle Rittenhouse verdict, which we honestly all knew

It just keeps going and then after a while we die -- Today we are going to do one of those issues where we get up to speed together on what is happening in big climate news, namely legislation in U.S. Congress and whatever in god's name

Philanthropy's refusal to fight the fossil fuel industry and the GOP is holding back progress on climate change -- Hello everyone today we have something special, you might call it a Crisis Palace classic in that it's all about climate change funding. Specifically it is an

I am also a we—social contagion in modern horror -- Fam I have been feeling a little sick the past couple days don't worry it is not COVID I took a test and PASSED. I am soldiering on though as this week's newsletter is an

'A world in which there is room for many worlds' -- Well I asked and you delivered. I didn't really know what to expect when I decided to do a reader participation issue. The response could have been complete crickets and I would have 100% understood.

I am passing the microphone to you—and giving some of you a little present -- If there are any real number-heads out there, you may have calculated that the next issue of this newsletter will be the 100th. (This one does not count because I say so.) That is

An interview with Sam J. Miller, author of The Blade Between and Blackfish City, on community organizing, how fiction can change the world, and finding joy during apocalypse. -- Sam J. Miller is a writer of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, all told with crackling prose, unforgettable characters, and a

Ministry for the Future tells the greatest story of our time, brilliantly, and with no resolution -- For years, there was this common refrain in the news media but also regarding books, movies, etc., that climate change is just not a topic conducive to broadly accessible stories. Chris Hayes notoriously

Humanity as a for-profit business but instead of getting fired for bad performance you just die -- This has been a big week for climate change news, not in the usual smoke blotting out the sun way, although smoke did blot out the sun in some places. But mainly I&

'Transition is inevitable. Justice is not.' -- In the past five years, the term "just transition" has become, maybe not a household term, but certainly pervasive throughout climate discourse. You see it in environmental justice groups' missions, academic papers, government policy, NGO campaigns, philanthropic strategies,