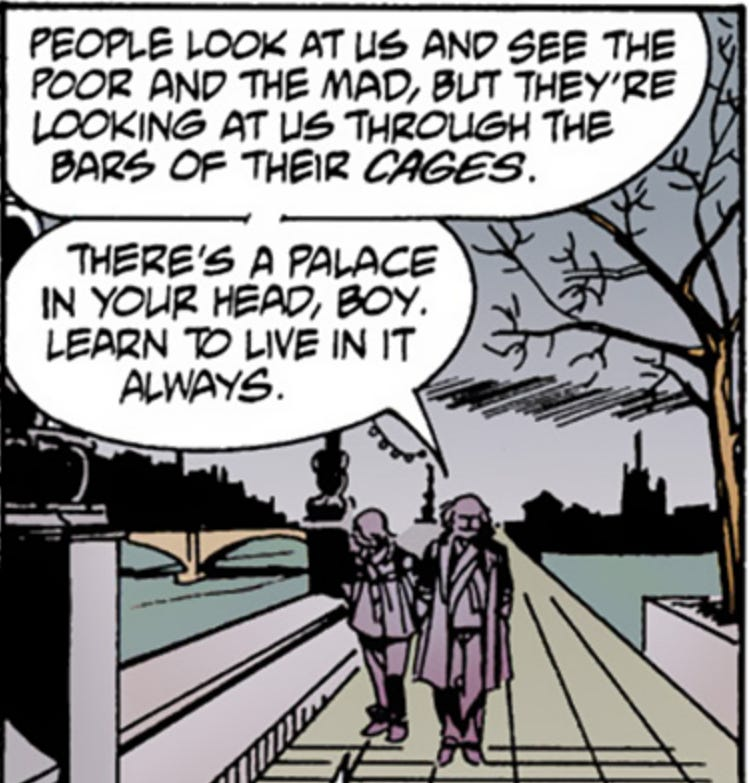

There's a palace in your head

The first chapter of a book I wrote about climate change and life during end times.

Well, happy new year, I guess. I didn't want this newsletter to be a weekly check in on everything horrible that's happening in the world, but it's tough when 2026 has already become the year when the U.S. government went all in on doing whatever the fuck it wants to anyone, anytime it wants, and nobody can do anything about it.

Of course, there are things we can do about it, and many of us are doing what we can, but all of this really makes you feel like you are losing your mind, especially when people are all over the TV and the internet telling you that you did not see the thing that you clearly saw with your own two eyes. Which is, of course, a murder carried out by an agent of the state, in public, in the light of day. The murder of a person named Renée Good, who was 37 and a writer and poet and a mother to three kids, before an ICE agent pulled out a gun and shot her in the face multiple times. That is really all you need to know about it because nobody should ever be shot in the face, but it has to be said that there is no justification for what the piece of shit did and anyone trying to tell you otherwise right now is missing either functioning eyes, a brain, or a soul.

All of this unfolded not long after this country's military killed 100 people and kidnapped the leader of another country, and went on the news the day after to say that we now own that nation and all of its oil. All in a matter of hours, not days, and who knows what country we will take over next.

To the extent that what's happening this year is new, it is probably in the shameless openness of it all. Throughout the resistance to the Bush-era wars, we were always trying to say that they were based on lies and that this is plain old imperialism and they were like no, no come on now. But now they go on CNN and are like yes we are doing imperialism and white nationalism, and they don't really give a shit anymore. Whether it's in other countries or in your neighborhood, they kill and kidnap people. If you don't like it they will shoot you in the face, block you from receiving medical care, and then drive away in their unmarked SUVs and chicken shit little masks.

But, of course, this stuff is also not all that new in concept, even if it is more extreme now than it has been during most of our lives. Our government has been toppling other governments in the Americas and far beyond for most of its existence. And our government agencies shoot people in broad daylight on our own streets, often to death, all the time. This was the ninth ICE shooting since September. Regular old shit-for-brains police killed 1,301 people last year.

Which is nothing to say about the routine kidnappings, the arrests, the detentions, and the deportations, or the horrors of America's modern day concentration or interment or whatever you want to call them camps. Last year, 32 people died in ICE custody. A report from Florence Project released today charged the nearby Eloy immigration detention center of "medical neglect, mistreatment during mental health crises, broken air conditioning in the midst of the Arizona summer, verbal and physical abuse by guards, and aggressive and invasive strip searches." Meanwhile, American cities are arresting their residents en masse, including in Tucson, for the crime of being poor and having no place to sleep.

They tell us that this ICE problem is a political showdown between Republicans and Democrats, a grudge between the feds and Minneapolis, but I don't know about that because it is happening everywhere, and the agency has been accumulating power and money under the last several governments run by both parties. As recently as June, 75 House Democrats voted to basically just announce to the world that they really love ICE.

So it's disorienting, to put it mildly, because it feels like this is in many ways the same fight against the constant beat down of American oppression that has been happening forever, but it also feels a lot worse. Like we've crossed into new territory where an ever growing portion of the population is going to now be vulnerable to detention or bodily harm or death at the government's hands on a day to day basis. And the people on the news are like, well, let's settle down here tempers are really flaring, Americans are so polarized we need to bridge our divides so we have chiller vibes during this ethnic cleansing.

And then we have to keep showing up and doing the things we always do. This is, after all, the kind of authoritarian government most people in the world have to contend with while they go about their business of being a human. It can be frightening, it can be enraging, it can be so stupid you can't believe it, it can be normal, it can be boring. But it's always there.

So I guess that is actually pretty thematically relevant to the main thing in the newsletter this week, which is the first installment from a book I wrote. It is based on this very newsletter, specifically issues that happened between 2019 and 2022, which was a crazy time, you guys remember that shit? I was going to set up what the book is about but that is dumb because this is the introduction to the book so it will all be explained.

OK the book part is starting now. It's kind of long but you can always open it up in your browser. Please read and enjoy.

Crisis Palace

Essays about climate change, life during end times, and what we build while the world is on fire

by Tate Williams

Introduction

The world is fucked up.

I know it, you know it. And yes it's always been pretty fucked up, but I think we all have a sense that somewhere along the way during maybe the last decade or so, things somehow got on a really bad track and everything got fucked up in new ways that are hard to precisely define, but are definitely worse than they have been at other times in our lives. And now things are not working the way they are supposed to, and they only seem to be getting worse, and we just keep muddling through with our daily lives, sensing that it’s always going on in the background.

It’s a feeling of brokenness, which we experience in the form of potholes or grocery prices, but it also dials up to much higher tiers of shit like, say, you and your neighbors getting priced out of your apartment building, or cops murdering someone during a traffic stop, or someone in your city getting picked up by police and just disappearing, or a relative dying from an illness they couldn’t afford to treat, or maybe even a town not all that far away from you being entirely consumed by fire. These are the kinds of events I’m talking about that are happening more often, and they all seem to be connected in some way. It’s definitely connected to Trump, who I will be calling Trunk from now on because I hate typing his name. But we all know it’s not just Trunk. It's more than that.

If you are reading this book, I’m guessing that you probably feel this way. But it is not just you and me. My sense, derived from the occasional polling numbers, but also just casual social media scrolling, is that more people out there are sharing this feeling that things are overall going in a not-so-great direction. This shared sense of crisis was heralded sometime in the 2000s by a cartoon dog in a little hat drinking coffee, but there are other cultural signals all the time, such as people campaigning for a meteor to be president, or when people say how did we get on this timeline, or worst timeline ever, or dumbest timeline ever. Or our New Year’s Eve tradition where we all say goodbye to the shittiest year ever, every single year.

Why do we feel this way?

I guess it’s a lot of reasons. I suspect it probably started for most of us right around Trunk o’clock, because honestly, how could you possibly feel optimistic in a reality that could produce such an unbelievably cruel and shit-having-for-brains era in a country that already held the running world record in both. I’ve never been a particularly optimistic person, but I imagine that first election made a lot of otherwise hopeful people feel like things were maybe not looking so good.

Then there was the pandemic, when we all experienced the untimely deaths of 15 million people in just a couple of years, over 1 million in the United States alone, coupled with the surprising hot take from a large portion of our country that sometimes people just have to die so the rest of us can get a haircut or go out to Buffalo Wild Wings or whatever. Covid brought with it the daily psychological toll of seeing refrigerated trucks full of dead bodies parked on the streets, or not being able to get within six feet of other humans. But also a bunch of weird unsettling shit like singing happy birthday while washing your hands, or not being able to buy toilet paper, or disinfecting liquor bottles in the sink before chugging their contents so you can get to sleep at night.

If I had to put my finger on the main driver of our collective dread, however, I would probably go with climate change. Even if others wouldn’t readily volunteer that assessment themselves—and a growing number of people, especially young people, would—I think there is a certain subcutaneous awareness that at this point, no matter what we do as a nation or a species, we can expect life on balance to continue to get worse. More people are going to suffer, lose their homes, die, etc. People are gaining more clarity on this reality every year, as we see a steady drip of headlines reporting hottest weather in hundreds of years, worst fire season in thousands of years, worst hurricane season in history. And with that awareness, I think we’re seeing this growing sense of despair that leads to cultural symptoms like apocalyptic fiction dominating pop culture. We turn climate change into zombies or white walkers or mushroom people or whatever, but we can just feel bad shit coming.

It’s not quite that simple though, either. Climate change is a big driver, but it’s not like everyone is running around talking about or thinking about climate change as this singular thing that is ruining all of our lives. That’s because we don’t experience climate change as a linear chain of events, or as an isolated phenomenon. In the military, which is made up of people who kill other people for a living and as a result have a pretty good sense of the ways people get killed, they refer to climate change as a “threat multiplier,” basically meaning that it’s not the thing that kills you, but it makes things that that do kill you worse, and that creates negative cumulative effects that interact with each other. So as we slide into an era of accelerating climate impacts, we get this bundle of breaking systems and endless varieties of death and suffering that are combining to crank up our overall despair and anxiety.

The fact that climate change and all of these breaking systems are interconnected is an underlying concept behind what we now call climate justice. It’s the idea that, while we can accurately describe climate change as an accumulation of greenhouse gases that is raising the average global temperature and causing sea levels to rise, that’s really just a pinhole view of what climate change actually is, and it’s not really how people experience it in their daily lives. They experience it in their kid’s asthma, or having to survive on plastic bottles of filtered water because they can’t drink what comes out of the tap, or flooded subway stations, or having to choose between air conditioning and dinner. And, crucially, they experience it at wildly disparate rates based on societal inequality.

Climate change has its greasy fingers on any number of societal shocks and stresses that aren’t typically thought of as environmental degradation. One of the biggest ways people experience this is through migration, as populations shift globally, but also within their own counties, cities, and neighborhoods. Masses of people having to flee one place and go to another is causing localized violence, housing instability, poverty, family separation, xenophobia, and armed conflict. It also contributes to colossal disruptions such as the spread of COVID-19 and the election of Trunk. The racial justice uprisings of 2020 were indirectly a product of the pandemic, along with environmental injustices in communities of color and Tribal lands, including Hurricane Katrina, the Flint water crisis, and the Standing Rock oil pipeline. The uprisings were directly a product of state violence trying to keep this increasingly unstable and outraged public under control, while keeping property and natural resources under lock and key.

So when we talk about the climate crisis, we are talking about something a lot more complex than an uptick in temperatures. But to properly diagnose the decline we’re experiencing, we also have to zoom out further and acknowledge that climate change is also not the origin of all of these problems.

As insidious as it is, climate is just one component of something much bigger. Some readers may be screaming at their little screens right now hey dumdum it is capitalism, just say capitalism already. Or they might have a different term to swap in there, like they’ll say “unrestrained capitalism” or “capitalism run amok” or “late stage capitalism.” Other popular culprits are neoliberalism, inequality, white supremacy, colonialism, patriarchy. And I would not disagree with any of those. But if I absolutely had to pick one, I’d probably say OK yeah, it’s just capitalism, you guys are right. I am sorry if you are reading this and you love capitalism. I realize it is still pretty popular.

Even capitalism is a little too narrow, though, itself serving as a shorthand for this whole bundle of ways in which the systems that dictate how we live with each other and the world around us are fundamentally fucked up. It’s an all-consuming order of existence, not merely a market-based economic model, that says our worst impulses—greed, competition, self-interest, fear, suspicion—are actually the best impulses, if not the only impulses that exist. That’s the thing that we can feel is broken. That is breaking us.

Figuring out what the bundle is, let’s call it the shitbundle, how we should understand it and engage with it as ordinary people, and how we can work to dismantle and replace it, is the absurdly ambitious subject matter of this book—a series of essays written by a nonprofit refugee and climate writer trying to reckon with a flurry of very bad things that happened between roughly 2016 and 2024, which I suspect will someday be considered the start of an era of sharp societal decline.

I mentioned previously some of the attempts in popular fiction to depict this decline that many of us are sensing, and one that I keep coming back to is William Gibson’s 2014 novel The Peripheral. It’s a story told in two different time periods, two stages of an apocalypse that people come to refer to as “The Jackpot.” There was a decent but canceled television show based on the book, in which The Jackpot is depicted as a string of bad luck and rogue attacks—cyberterrorism, a virus, a nuclear explosion. But in the novel, it’s less a random chain of events, and more like a bunch of human failures piling up. It’s more explicitly caused by climate change (the term not uttered in the lone season of the show), combined with political violence, drought, famine, and poverty. In short, we just fucked everything up and it all fell apart in a series of cascading collapses. That feels to me a lot like what we’re starting to go through, and what this book is grappling with.

So I know the subtitle says this is a book about climate change, and it is, at least a lot of it is. But the more I have written about climate change and its many comorbidities, the more I feel the Jackpot-ness of our current moment, the shitbundle in which all of these system failures are connected, like when Lady and the Tramp are eating spaghetti and surprise it turns out to be the same spaghetti.

What Is Crisis Palace?

You’d be forgiven for thinking that this book is just a big firehose of dread and despair, and it kind of is sometimes. But it’s not entirely, and that brings us to the title of the book, which may or may not be self-explanatory, so I’ll just explain it. They say the mark of a great joke and book title is one you have to explain.

To be perfectly honest, the name Crisis Palace, when I first came up with it, meant absolutely nothing. It came from one of those memes where you use your initials to pair random words that make the name of a level in the video game Sonic the Hedgehog. I’m not making that up, it’s literally where that combination of words came from, so stupid I know. But it became almost like the Tarot for me over the years, this random combination of imagery that came to hold a lot of meaning.

I swiped the name from that meme because I needed a title for the weekly newsletter that would eventually yield this collection of essays. I started it up in 2019 back when newsletters were really popping off and before they became a way for magazine writers to become wealthy by attacking trans people. And my newsletter was one of the good ones. It started in part just as a way to have a weekly writing practice, and in part to pull together the threads of writing and activism I was doing at the time. I was working mostly as a journalist covering climate change-related philanthropy and nonprofits, which I found important, but it was only scratching the surface of the things I was struggling with. So the newsletter was a way to write about these interests and concerns in a way that felt natural, and using a looser tone and structure than I was ever able to as a paid writer.

The period of the newsletter that this book is drawn from spans from 2019 to 2022, so we’re talking about deep into the first Trunk administration, then into the 2020 election and its aftermath, the pandemic, Black Lives Matter, and ever-worsening impacts of climate change. Over time, I found that issues of the newsletter were getting longer and longer, and covering more and more topics, but they still had a certain amount of coherence that I came to think of as Crisis Palace-y. My favorite description was when I heard someone describe it to a mutual acquaintance as a newsletter “about climate change. But really about what it’s like to be in the world right now.” And for me, just as much as that messy bundle of interconnected disasters, Crisis Palace came to represent a certain dual nature of living in these times.

The thing that is most compelling and true-feeling to me about William Gibson’s Jackpot is that not everything gets bad or stays bad, universally, all at once. It’s a vastly uneven apocalypse. So in the distant future timeline, long after The Jackpot, there’s a kind of bleak coldness in that huge swaths of the population are dead, civilization has been replaced by an AI-run government and dueling crime families jockeying for wealth. But at the same time, you wouldn’t call it a hellscape. It’s frightening in its own way, but perfect in other ways—a utopian dystopia. Gibson depicts a London that is regreened, with a system of rivers flowing throughout lush parks and glass skyscrapers. The world post-apocalypse sounds less like Mad Max and more like a semi-abandoned Vancouver. There’s no disease, and by all appearances, humanity did sort of solve climate change. It just happened way too late, and at the expense of billions of lives. In the earlier time period of the book, we see a much greasier, sicker world from right before the collapse. But there too, characters still spend time with families, friends, partners, protect each other, help each other, put their ragged tech to the best use they can to make their lives as tolerable as possible.

This is the truth of living in end times, which is different than what we see in a lot of apocalyptic fiction. I interviewed science fiction author and activist Sam J. Miller for the newsletter, and he brought up his frustration on this topic:

I mean, my particular axe to grind with a dystopia/utopia conversation is that life right now is utopian for many people. There’s lots of people in the world who enjoy unimaginable comfort and abundance. And there’s tons of people for whom life is utter dystopia, rivaling anything in The Walking Dead. And working with homeless folks in New York City, I was able to see that every day. So I don’t think there’s ever been a point in human history where that hasn’t been the case—utopia for some and dystopia for more. And it’s also hard for me to imagine a future where that’s not the case.

In the worlds Miller builds, particularly in his climate change sci-fi novel Blackfish City, there is a vast disconnect between the haves and have nots. But I also love the way he portrays the joy that bleeds through in the lives of the book’s villains and protagonists alike. That whiplash between dystopia and utopia is another cause of our modern disorientation. Because just as we can sense things are getting worse, we can also look around and see other things either being not that bad, or in some ways getting better.

I think this is a characteristic feature of our times, which we experience in a couple of ways. First, there’s the not-so-great way in which obscene comfort rubs up against squalor—20-year-olds living in shiny towers, paying $100 to have a poor person bring food from a four-star restaurant to their doorsteps so they don’t have to catch a virus or talk to the people sleeping on the sidewalk outside. Rich guys buying self-driving electric cars that kill pedestrians, while poor people choke on exhaust from the fossil fuel plants that charge them up.

The other version of it is the way that moments of self-improvement and societal improvement are interwoven with disaster. In our neighborhoods, we see it in mutual aid groups, anti-capitalist spaces, and cooperatives thriving within the borders of otherwise failing urban environments. As individuals, we experience emotional and intellectual awakening, a utopia that fires in our neurons and runs through our veins.

For me, that duality is the main the concept of Crisis Palace. These essays are about finding pockets of abundance in a world of suffering and setting it free. They’re about the paradise that we build amid decline.

Productive Pessimism

Since we’re going to be talking so much about living in end times, it’s probably worth it up front to explain what exactly I mean by that. If for no other reason than to acknowledge that it is impossible to predict the course of human history and there’s a chance that someone is picking this thing up at a time when life is more or less fucking rad for everyone and whoopsies so much for my little musings about the end of the world.

If that is indeed the case, I would honestly be super excited because there is nothing better to be wrong about than global catastrophe, and that means right now I’m off somewhere living my best life getting into woodworking or crochet.

I suppose there is decent reason to believe that things are not going to get as bad as I’m fearing in most of the pages that follow. For one, history makes a pretty good case for the world not ending. If you were to read the entire human story as an epic tragedy, you’d be very disappointed by a messy narrative with vast stretches of not much happening. Most of our lives, too, are pretty uneventful most of the time. On the same day that a chunk of ice the size of Rome broke off of the continent of Antarctica, I had a couple of uneventful Zoom meetings and I probably cooked dinner and watched TV. It was a Tuesday.

Part of the impulse to believe that the world is ending is a craving for a story of some kind to make sense of all this. It can be a narcissistic urge to imagine a narrative of humanity that peaked in our own brief lifetime. It an also be a tool to frighten other people into servitude. Writing about the end of the world often employs foolish levels of certitude and judginess. Since we’re using Gibson’s model of apocalypse here, we might also look to his own skepticism toward the concept. In his 2006 essay, “Time Machine Cuba,” Gibson wrote about his childhood discovery in the 1960s of the World War I-era sci-fi of H.G. Wells, all while the Cuban Missile Crisis was unfolding in the background. He was left at the time with the conclusion that the world must be about to end, and while reading Wells’s warnings about the future, awaited the inevitable nuclear war. In 1921, Wells wrote that he would one day look back on the catastrophe he predicted and say, “I told you so. You damned fools.” Gibson refers to the author’s tone as that of “the terminally exasperated visionary.”

I suspect that I began to distrust that particular flavor of italics when the world didn’t end in October of 1962. I can’t recall the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis at all. My anxiety, and the world’s, reached some absolute peak. And then declined, history moving on, so much of it, and sometimes today the world of my own childhood strikes me as scarcely less remote than the world of Wells’s childhood, so much has changed in the meantime.

I worry that, at times, I write in the italicized tone of H.G. Wells’ damned fools. It’s the tone of the naïve futurist for whom the world is never good enough, viewing the course of history through the distorted lens of his own anxieties. Still, even Gibson, in his later years, has walked back his distrust of apocalyptic thinking. When his 2020 novel Agency came out, he would frequently talk about how he began to struggle to envision any future at all, much less a good future, in a post-Trunk reality. I saw him give a talk in Cambridge that year, and he said the post-2016 world had become “so stupid he often thought he must be dreaming.” And every week it seemed to get stupider than the week before. In a 2020 interview with Michelle Goldberg in the New York Times, he confessed that while he used to consider himself an optimist, it was getting more difficult. “Since the end of the Cold War, I’ve prided myself on being the guy who says, eh, don’t worry, it’s not going to happen tomorrow,” he told Goldberg. “And now I’ve lost that.”

In other words, yes, history does seem to chug along, and while it’s a natural human tendency to fear that the end of humanity is not too far on horizon, the odds are pretty good that it will not happen. That the world will not end. And yet…maybe it will?

Between climate change, artificial intelligence, zoonotic and/or lab-engineered disease, and nuclear stockpiles, there is a non-zero chance of the literal end of us coming about. To accept this possibility can be lazy doomerism. Or it can be a form of productive pessimism that we can use as a tool. It allows us to roll that worst outcome around in our mouths to see how it feels and whether it’s something we want to drink a full glass of, or perhaps take another look at the menu.

Whether the literal end arrives or not, there’s another version of the idea of apocalypse that is less reliant on eradication, and therefore, far more useful in terms of how we live our own lives. The key here is to understand that apocalypse is not a singular event. In fact, there have been countless apocalypses, and we’ve lived through them all. You might think of it as the end of a world, as opposed to the world. It’s the form of end times in adrienne maree brown’s podcast “How to Survive the End of the World,” the title of which telegraphs that an apocalypse is not an end, but a collapse that is also the birth of something else. It’s an idea that has been put forth by Indigenous authors: that for many Native peoples, European colonialism was the literal end of the world, a systematic attempt to erase a culture. As Rebecca Roanhorse, an author of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo descent, put it, “We’ve already survived an apocalypse,” and as Indigenous activists frequently remind us, “We are still here.”

Make no mistake, this world will, without ambiguity, end as a result of climate change. The world we were all born into, where the oceans end at a particular point in the sand, and where every year we see the flowers bloom and the frost melt at a certain time of year, is in the process of dying. Once we’ve come to terms with the fact that worlds as we know them do and will end, we can start thinking about what to do about that.

I absolutely have not figured that out, but I do feel like I maybe got a little, teensy bit closer over the course of writing these essays. I don’t have the solutions to the problems discussed here, but I hope I’ve gotten closer to a certain perspective that might help me to start identifying them. That outlook is characterized by a few principles that I find myself believing, at least for now. That radical change, not incremental policy or technological fixes, is necessary. That radical change is possible and it actually happens more than you might expect. That we’re never going to fix humanity or society, but we always have to keep trying. And that the key to making the world better comes down to power—challenging it, building it, shifting it, and using what we have.

This last point about power is one that I kept coming back to in all of these essays, so much so that I ended up roughly structuring the book around the concept. I think it is necessary to engage with the end of the world using a strong power analysis in order to shape our future into something that better serves us all. I also think power is a useful concept as a self-help tool during these difficult times. Speaking for myself, so much of the negative feelings I experience as a person in the world right now could be described as powerlessness. Every day I see something horrible happening around me, and feel like there’s nothing I can do about it. But of course, that’s not really true, is it? The reality is, we have lots of power, and we have lots of points where we can access and manipulate the various forms of power that flow around us.

By viewing these crises and their solutions as a matter of power, I think we can better understand where we fit within them, and generally feel a little bit better about what we are able to do about them. So in organizing this book, I grouped the chapters together around four forms of power:

The Individual

Americans are obsessed with individual behavior and responsibility, and it has not served us well. In climate change, economic inequality, even electoral politics, we are constantly told that what matters is what you do as an individual. That’s a dangerous misdiagnosis, but the other hand, there’s been an overcorrection to it that tells us there is nothing we can do as individuals that matters. These chapters challenge the dichotomy between the individual and the collective, and wrestle with the question of what the individual can do to create collective solutions.

Money

For a made-up concept, money is the most tangible form of power. In amounts big and small it makes things happen. People who have it in large sums set the world’s agenda. Even anti-capitalists will be hard-pressed to make anything happen without it. A lot of activists hate this, but there it is. These chapters discuss philanthropy, elite environmentalism, and cultural worship of wealth, and how we can use money as a tool to combat those forces and challenge capitalism.

Movements

Individuals and money can get a lot done, but nothing is more powerful than massive numbers of people pushing the world in a particular direction. These chapters explore the purpose of protest in social change and challenge centrist criticisms of activism and radical social movements. Here I pose that a life devoted to making the world a better place can be a form of relief and redemption, even when it doesn’t seem to be working.

Community

In the past year or so, I have not exactly retreated from the work of electing better government or advocating for better policy. But in terms of what I can do, and how we’re going to survive this apocalypse, I’ve found that our efforts are much more useful when directed at our own neighborhoods, which have immediate benefits and trickle up to large scale change. These chapters takes on the messiness of local politics, organizing, and mutual aid efforts, and all of the rewards they can bring.

The Future

This last section is kind of a cheat so that I can write about science fiction, but how we envision what’s to come is a source of power in itself. Climate change makes it difficult to engage with that future, disrupting our expectations and stretching our awareness into geological timescales. These chapters look at how we might imagine what is ahead, and how that allows us to set the terms of what’s possible.

—

So there’s a little map of what’s ahead. A map to what, exactly, I’m not sure. The following essays are full of far more questions than answers. Sorry about that. They’re also, I’m quite certain, loaded with contradictions, half-baked thoughts and feelings, frustration, exhaustion. There are things in them that I probably have changed my mind about by the time you’re reading them. In a way, that’s what I’m most proud of in this collection—that it’s not neat or slick or the kind of seamless thesis you might get from a different kind of book. Frankly, it’s all kind of a mess. But in the best way possible, because that’s how it feels to be a person in the world right now.

Above all, I hope this book will be helpful to anyone who is similarly frustrated with the way things are, who is having a difficult time understanding how they fit into a catastrophic future. I hope it is comforting, and maybe a little empowering, in a time when it is too easy to feel powerless.

OK there you go, we're off the races with the book. I really do hope you had a nice holiday season and New Year celebration. I ate a lot of cheese and played some frisbee golf and watched like 100 movies.

Hang in there, don't feel guilty if you give yourself a little treat now and then, and try to get enough sleep.

Tate