85: Raze and rebuild 2

What gets built has little to do with the interests of the community and everything to do with what builds more wealth

--

The sun is shining, the masks are off, and the sounds of gentrification are ringing in the air.

In any given direction from where I am sitting in my frankly uncomfortably humid apartment office in one of Boston's outlying neighborhoods I can hear nail guns, power drills, table saws, all grinding away during every waking hour. The hot smell of overpriced lumber is strong, and the streets are lined with blue toilet boxes and dumpsters overflowing with the guts of century-old homes.

People are done with the pandemic and we are in the short window of prime outdoor labor weather and the housing market is reaching peaks that rival the 2000s bubble, so it seems as though every other address in the city is being redeveloped, every triple-decker remodeled, every eyesore being razed and rebuilt.

The housing market is scorching nationwide, although it is particularly out of control in Boston. In April, the median price of a single-family home in the city hit $765,000, and the price of a condo hit $622,000. Remember that one neighborhood close to me where there was the condo with an "open concept" bathroom? Well in that neighborhood right now there is burned out husk of house that's on the market for half a million dollars. Even in nearby Providence, which has long been one of those mid-sized towns that can provide an escape for East Coasters fed up with the worsening exclusivity of our larger cities, prices are rising and supply is tighter than ever.

Way back in one of the early issues, I wrote about a house a couple of doors down in our half-fancy/half-not-fancy neighborhood that was scheduled for demolition. For years this was a rental property home to lower income tenants and owned by a slumlord who lives out in the suburbs and generally left it in disrepair. Apparently, Jerry, his name is Jerry, maybe got tired of dealing with tenants and saw what they call in real estate "an opportunity" so he decided to tear it down, rebuild, and sell.

I got a note in the mail a couple years back about it because we live nearby and were invited to some meetings to discuss the project, during which there was a lot of talk about mostly code variances and also a group of neighbors who were very worried about a big tree on the property far more than they were worried about people who lived there. "We're all here about the tree" one of them said, the fuck we are some of us said back, because a handful of housing justice gadflies like myself (at what age do you go from activist to gadfly?) attended to yell at the city about displacement and lack of affordable housing.

In Boston, new projects only need to include a percentage of affordable housing if they have 10 or more units, the kind of project that's impossible in many neighborhoods. The affordable housing is also not even that affordable, and the developer's requirement can even be punted out of the neighborhood to be built offsite in some unsightly part of town. Those are some of the many factors that are contributing to the city's problem—that even as Boston scrambles to create more stock and meet housing demand, people are constantly getting kicked out and priced out and the new units that go in are totally inaccessible to most Bostonians.

Anyway, that project near us of which there are many just like it got put on hold because there was a pandemic you may be aware, but it's back on now, 100% displacement, torn down in a day or two, currently a construction site and soon the units will sell for god knows how much.

There used to be a house here.

Housing is an important issue for a lot of reasons, obviously, including that it determines everyone's wellbeing and dignity and quality of life, but also because what we build where determines our energy use, with buildings accounting for some 40% of energy consumption and also dictating how we travel. It's also a very frustrating issue for many reasons. For one, there are some very clear (clear to me!) policy solutions that seem to never be able to pass due to deeply rooted power structures. That is why, for example, some 75% of land in major cities in the United States is zoned for single-family housing, a form of exclusionary zoning that effectively bans poor people and people of color from living in most neighborhoods, while institutionalizing sprawl and excessive energy consumption.

Housing is also frustrating because decisions are often oversimplified into some very unhelpful binaries that rarely represent the reality on the ground. The big divide is YIMBY vs NIMBY, people who either shout "yes!" or "no!" to the prospect of things being done in their proverbial backyards. A NIMBY, as it goes is a rich, often liberal homeowner who doesn't want to see new housing built because they want to protect their neighborhood. A YIMBY is usually a very nicely dressed professional who says all development is good due to their shrewd understanding of markets, this is a simple supply and demand problem you see. And these are the two sides.

You know I hate to do a both sides, but honestly, this is a both sides kind of thing, because sometimes the right answer is NIMBY and others times it's YIMBY. And sometimes YIMBYs and/or NIMBYs are part of the problem.

For example, as someone who sometimes goes to community meetings to yell at the city about new condos, you might gather that I am a NIMBY. But I am totally not! I love new housing. I basically wish every structure in the city had new housing units built on top of it. I come from a family of builders as does ~*my wife*~ and I even wanted to be an architect for much of my young adulthood until I realized it was way too hard which in retrospect was probably a bad career decision. So, pro-building over here.

In fact, as I was getting riled up about Jerry's raze and rebuild job, I was also getting all red ass about people in the neighborhood who were opposing a new mixed-income housing project just down the street. The city wanted to develop a piece of public property into affordable housing, and townies and business owners came out in full force to stop the plan. We went to this packed information session in a beer hall in which the city tried to clear up misconceptions and defuse the anger over the project and there were people literally just screaming at these poor city planners, about how people were going to get murdered and people in the new apartments would spy on us through their windows and all of the thriving businesses in the square would actually just close and be boarded up and then things would start catching on fire. And they did it they killed the project!

And now it is happening once again, just down the road in Jamaica Plain, one neighborhood over you know where the open air toilet condo is. There is a stretch of road that's been under heavy development, with market rate condos shooting up alongside either end of the street in recent years. But a low income housing development was slated to go in, and a neighboring property owner decided to SUE to stop it from happening because he says it will hurt his business. The business, in case you were wondering is a beer garden. (In fact the same craft brewery from the beer garden where we attended that city information session. You know the kind of place, where you drink beer on an old barrel as a table and young dudes in tight clothing get drunk and talk about soccer while their toddlers run around and bug perfectly nice couples just trying to get a buzz on.)

So at the time, it was just the landlord suing (his name is no joke Montgomery Gold), and the brewery owner tried to stay out of it. But he made some guarded comment that made it clear he was definitely against the housing project. And now there is another affordable housing project in the works, this time for very low income seniors for Christ's sake, and the landlord is suing once again, and this time so is the brewery owner!

As you can imagine, they are getting a lot of backlash, but there are also a ton of people in local facebook groups etc, as always, doing endless mental gymnastics to find reasons to oppose affordable housing. While there is indeed a lot of complexity in housing, honestly sometimes people just don't like the idea of poor people moving in. In any case where a developer is trying to build a project that serves lower and middle income people, there are always concerns about variances, concerns about parking, concerns about traffic, concerns about building height, concerns about the color of the building, concerns about the type of siding that will be used, concerns about landscaping, concerns about disruption to business, concerns about safety, concerns about privacy, concerns about "who this will bring to the neighborhood." The objections are numerous and the accommodations are never enough. It is always the wrong project in the wrong place at the wrong time. They never oppose affordable housing, they just oppose THIS affordable housing project.

So I guess my point is, there are good reasons to fight for new development and there are good reasons to fight against new development. Sometimes a project is a great idea and sometimes it's shit, and the decision about whether it gets built or not always seems to have nothing to do with the best interests of the community and everything to do with what will build more wealth, with the final call always made amidst and in spite of a cacophony of neighbors screaming at each other from folding chairs in the basement of some community center.

So not only do we have a frustrating problem of special interests preventing good policy that would make things on balance better for everyone, we also have a problem in which we seem to have no good way for communities to effectively make planning decisions. On the latter point, I truly do not know what the solution is. Often my go-to answer to these kinds of decision-making problems is more participation, more democracy. But to be honest, deliberative processes on housing and land use are often total disasters and end up either derailing good projects for bad reasons, or creating an irrelevant side show.

In some parts of the country, the housing problem has become so bad that they've resorted to just railroading local opposition. For example, in Santa Rosa, when the combination of wildfires and the pandemic brought the area's homelessness problem to new levels of severity, elected officials charged ahead with a plan to build a tent city to house 140 people at a local community center. During a public meeting, hundreds of residents screamed at politicians for hours, trying to stop to the plan.

But they did it anyway, as outlined in a recent article in Next City. “Go ahead and vote me out,” one city councilor said. "You want to shout at me and get angry? Go ahead." And once it was built, people in the community actually ended up embracing the project, dropping off donations and spending more time at the center. As a county supervisor put it, they just had to take the risk. “We can’t just keep saying no. That’s been the failed housing policy of the last 30 to 40 years. Everybody wants a solution, but they don’t want to see that solution in their neighborhoods.”

While not a housing policy exactly, in my neighborhood there was a nightmarish traffic problem in a major two-lane thoroughfare, so the city wanted to take out a lane of parking and make it a bus priority lane. Had they gone through the usual series of meetings, people would have lost their minds. People love parking so, so much. But the city just did it. First, with a bunch of cones to try it out and then eventually with paint. And when people complained, the city would point out that traffic is now moving way faster and a large percentage of the people parking in those spots it turned out were commuters coming in from outside the neighborhood.

On one hand, I love these sorts of guerrilla projects that either involve taking political risks or making temporary improvements that can prove themselves before they become permanent. There's a good case to be made for giving local leaders some latitude to make these moves.

But I don't know, it also feels like that's not really it either, you know? Like there has to be a way for communities to chart these paths, and we can do better than leaving it entirely up to representatives or municipal staff, who often defer to developers anyway. Part of me has to believe that the problem isn't the participation itself, but how the participation is done, and whose voices are being heard when these projects come up. Because let's be honest, most of the time what we're seeing here is not just neighbors screaming at neighbors; it's privileged neighbors screaming at other privileged neighbors, over the best way to protect their own chunk of wealth, which is not really much of a community meeting.

It's something we need to get better at, because these changes end up affecting us all; even gentrifiers are getting gentrified these days. I should know—a few days ago, our landlord came knocking on our door saying he'd like to come by in a few days and take some photos of the house. A new opportunity has come his way, it seems. If he can get the right price point that is.

--

Reading

Related, Sam J. Miller, who wrote a fantastic climate sci fi book Blackfish City, recently came out with an excellent new book, The Blade Between, which he calls a "gentrification horror novel." I love Miller's books because while there are clear protagonists, for the most part there are no clear good guys and bad guys. Along with being a fiction writer, Miller spent much of his career as a community organizer working on housing, and while that gives his writing a clear sense of justice and empathy, it also gives it a clear sense of complexity. As he writes in Blackfish City, "Every city is a war. A thousand fights being fought between a hundred groups."

That message lives on in The Blade Between, which is about a young artist returning to his fast-gentrifying hometown of Hudson, New York, and the turmoil that follows, made worse by the ghosts of slaughtered whales and other angry spirits. The book is about the internal conflict we all feel about the places we are from. "It's OK to love something that you hate, just like it's OK to hate something that you love," one character concludes.

But it's also about the way these places are changing, often becoming unrecognizable and at the great cost of people who live in them. The people of Hudson are all shattered at varying levels, often as a result of an economy that has left them behind or chewed them up, and the resulting addiction, eviction, fire. But the book is also not unsympathetic toward gentrifiers themselves, recognizing the guilt, pain, and frustration in not wanting to be complicit in what is happening in our cities. It direct its anger mostly at the cycles and systems that need to be torn down and rebuilt.

As Miller writes about his book, in a recent essay for Tor.com:

"...my prime directive was crafting an ending that raised up the possibility of a third path forward being forged, through dialogue and hard work on both sides. In the modern-day housing market, there are no ghosts. No monsters. Only people. And if we want the future to look less like the horror story of hate and violence that is our history, we all have to make peace with trauma, and our role in it, and the privilege and pain we possess in relationship to it. And our power to create change."

--

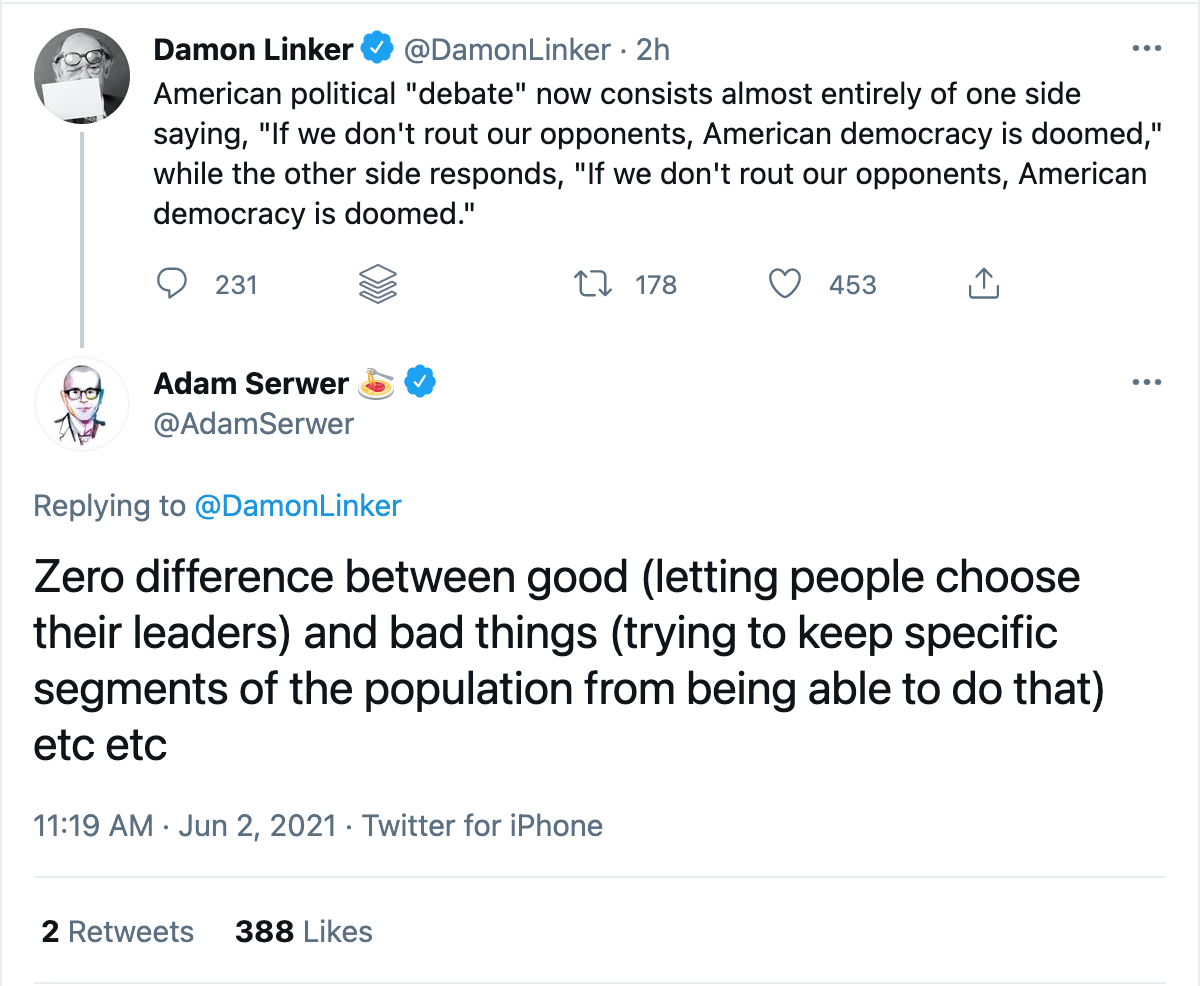

I don't know about you guys, but lately I have been feeling like all of the debate and discussion and progress and polling that we've all been watching in a bunch of different areas since January might be totally meaningless in the end because there's a machine working nonstop in the background to dismantle democracy and our next federal government will basically be interminable Trumpism elected against the wishes of a large majority of the country. And now some movie and music picks.

--

Listening

A while back I shared a song from Soft Sounds From Another Planet, but just today there is a brand new album from Japanese Breakfast so here is a single from it that I have been listening to.

--

Watching

Still watching movies only, including currently slogging through The Master which I'm considering bailing on because it's very boring but let me know if I should stick with it. One good movie I watched recently was Train to Busan which is a zombie movie that is very intense and emotional, in part just imagining what it must be like having intercity high speed rail.

--

A fast one this week, old school CP, fast and furious which is another movie I just watched, Tokyo Drift, to be exact. Do not worry about our house, we will be fine either way. It is just a wild time right now in these leafy streets, you know what I'm saying?

In other news, our old little dog Jacoby, you know the one who was having trouble sleeping, it turns out the poor little guy does have dementia, doggy dementia they call it. Apparently in old age, dogs sometimes get confused as to what time it is and they have a hard time following a normal schedule. So we're trying all kinds of medication to help him sleep and let him relax in his golden years.

I hope you readers are able to relax too, whether you are in your golden years or not. And I hope you can get there without eating half a gabapentin and half a trazodone squished into a piece of hot dog every night. But even if you do, that's cool with me I support it.

Tate