It's everybody's fight

A conversation with Liz Casey of Community Care Tucson on the power of mutual aid, the cruelty of immigration detention, and how city officials are failing us.

For the first interview of the rebooted newsletter, I sat down with Liz Casey, my fellow organizer in Community Care Tucson and a longtime social worker with immigrant justice group the Florence Project. CCT is a mutual aid collective providing food, water, and a wide array of other resources to anyone in need in Tucson, Arizona for the past five years. I've been involved since 2022, and Liz was one of the early members dating back to the start of the pandemic.

The best way I can think to describe Liz is that she is a born fighter. She is driven by an unwavering sense of justice that has led her to any number of frontlines in the community over the years, whether that's shutting down the construction of a new Pima County Jail, protesting ICE raids on the streets of Tucson, or relentlessly calling out the city government's cruel treatment of the unhoused.

She is also a very kind and caring individual, and a true believer in the power of mutual aid as a way to provide the support that our institutions repeatedly fail to deliver, but also to chart a path toward a more compassionate society. In other words, her compulsion to fight harmful systems is rooted in her sincere care for other people. And finally, she is a good friend and a cool person. Here's our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

This is going to be kind of weird, because I'm gonna be asking you some things that I kind of already know about you. So just pretend I don't know. Okay, so start out by telling me how you ended up in Tucson. I know you have family here, but how did you end up here, and how did you end up doing your job?

I was at Boston College for social work, and I focused primarily on a lot of social justice issues and a lot of immigration and refugee rights issues. And, yeah, I had family here, and I always visited them. I always loved the culture and like being near the border. So when I was in grad school, a professor knew somebody who was in Tucson. So he linked me up with her, who linked me up with the Florence Project, and then I was hired out of grad school.

Can you describe what social work is, just broadly speaking? What's your kind of day to day goal and the stuff that you do in your job?

I feel like that's a different answer for different people. But one thing that stuck with me was one of my professors at one point said that the goal of social work is to work yourself out of a job. Social work shouldn't exist because the need shouldn't be there. So I pretty much latched onto that. And no matter what I was doing, the purpose was to essentially dismantle the systems that were leading to your job being necessary, so leading to your clients being oppressed. So for me, that's the ultimate goal of social work and obviously, day to day, being in solidarity with folks, meeting people where they're at, not trying to put my own or our own expectations of what somebody's life should be on them.

That's interesting, because that sounds more like mutual aid than I would have thought.

Yeah, that's how I see social work. I mean, I think everything I do is considered social work and everything we do at CCT is social work, and that's what social workers should be doing. I mean, you can really go anywhere with it and do anything. But for me, it's very much about dismantling the oppressive systems.

So at the Florence Project what is your day to day job like?

That's changed a lot over 10 years. For a while it was just meeting with folks who were in more vulnerable situations in immigration detention. So when I started, there were people who were pregnant, people with severe medical issues, people whose kids were taken by [Department of Child Services], sometimes only because they were in immigration detention. So we tried to assist people with their DCS case or tried to advocate to get them out of detention.

And then it switched after a couple years. Essentially, we created our own team to work with the people who had a serious mental illness, and that ended up becoming a lot of community case work. Because for a while, a lot of our clients were actually getting out of detention, but for those specific cases, we continued to represent them in the community in Arizona. And the way I describe it is that I became more like their advocate, helping them with things like shelter and housing, health care and mental health care, issues with police. I wasn't their one social worker for one thing, which I feel like is how a lot of the systems work. We really became their one advocate that tried to connect all of these systems so they weren't just siloed.

Now it's switched a little bit. I'm doing advocacy, so basically documenting abuses and conditions in detention right now, and helping people file complaints to different agencies, and really just trying to document for reports, for the media and for public, what's actually going on in detention.

What is the average person that you work with like? Where do they come from? How old are they? Do they have families?

In detention, it's literally everybody. Several countries represented, just people from everywhere. All ages. I've worked with very elderly people who are in detention. I've worked with 18 year olds who are in detention. You know, some people have lived here for years and years, but for some reason—and the immigration laws are extremely confusing regarding when somebody becomes deportable—they ended up getting picked up by police and then picked up by ICE.

But generally, there is no typical person. It's just everyone. You can go to the border and ask for asylum and then be put in detention. You could have lived here for 30 years and then be put in detention and have your whole family here. There's a couple people that we worked with who really just didn't have any family support. So yeah, it is a huge range of people.

How often is it people who came here because they were under direct threat of something where they were from?

I think the majority, yeah, most people are seeking asylum. For one reason or another, they can't go back to their country.

When people end up in detention, it sounds like it's a mix of being picked up at the border and then also just being in the United States and getting ensnared for something.

Yeah and it seems extremely arbitrary from what we can tell. Obviously, now it's different, and people are being picked up at their jobs, on the way to work. But yeah, you can go up to the border, up to Border Patrol, request asylum, and they can still put you in immigration detention if they want, or they can release you. It seems completely arbitrary. I'm not sure if there's a system or not.

What is the difference between working with people who say, were incarcerated in prison or jail and those in immigration detention? Or is it kind of the same thing in terms of the challenges they face?

We work with a lot of people, especially people with mental illnesses, who are in jail and prison. But all these systems overlap, so the people who are in jail and prison are often involved in the shitty mental health care system, or are known to police because they have mental health crises, or they're self medicating, they're using drugs.

So I don't know, all the systems are overlapping so much for people. But, I mean, the setting is also extremely traumatizing so people are still facing these same barriers if they are just in immigration detention, as people in jail and prison. They're in uniforms based on their security threat level, which is also bizarre, because it's civil detention. Everything's barbed wire. I have to go through two doors where you press a button and have to be buzzed in just to get inside, you're locked in yourself. I mean, it's run just like a jail.

I suspect a lot of people, who maybe have not great opinions on immigration, probably have the impression that everybody who's in detention is basically a criminal. I think a lot of that was the Obama administration's framing of, we only deport criminals.

Yeah, and using private prisons to detain people who are immigrants, and it makes them look like they are criminals. But the thing with immigration detention, is that nobody is there for a criminal matter. So if there is somebody who has a criminal charge and gets picked up by police, they'll go through the whole criminal justice system first. So everybody who is in immigration detention is there for civil immigration proceedings, even if they have a prior conviction. None of that system is part of the immigration detention system. Nobody is there for a crime.

And you were saying on the back end of things, when you leave any kind of incarceration, you've been through a lot of trauma, and you face a whole set of health, mental health, legal challenges.

Yeah. I mean, this is depending on people's experiences, and you don't want to compare traumas, but I've had people who have been in prison say that there's more to do in prison, because they're serving their sentence, they have some groups they can go to. Not that it's fun, but in immigration detention, you're just languishing indefinitely. There's very little recreation available other than TVs. There's not really anything else to do.

What are the different outcomes that can happen to people who are in immigration detention? What's the best case scenario and what's the worst case scenario?

It depends what what the goal is. So you can go through your whole immigration detention case there. But it's not really like you win or lose. It's very confusing, but now what we're seeing is that under Trump, folks that have won withholding of removal, which means you are not at risk of deportation to your home country but have not been granted asylum, those people are sitting in detention waiting to be deported to a third country. So if the judge says you haven't won asylum, but I'm granting you withholding of removal, the government is now looking for a different country to just drop people in. They're essentially trying to drop people in countries where they've never been and don't speak the language. We have not seen that before.

On that note, what has changed in the time that you've been working there, starting under Obama, then Trump 1, then Biden, the Trump 2?

One thing I always tell people is that, when I started, there were a lot of pregnant women in detention. That was all under Obama. That was always extremely sad. You know, people who are very pregnant and their backs hurt because the mattresses are so shitty and you can feel the wires and stuff underneath them, so their back was just killing them all the time. It was horrible. The food was terrible.

And then, yeah, I mean, under Trump 1, it was definitely bad. Things were changing a lot, like immigration laws, during the first Trump administration, but nothing like what we're seeing now, just decimating people's rights.

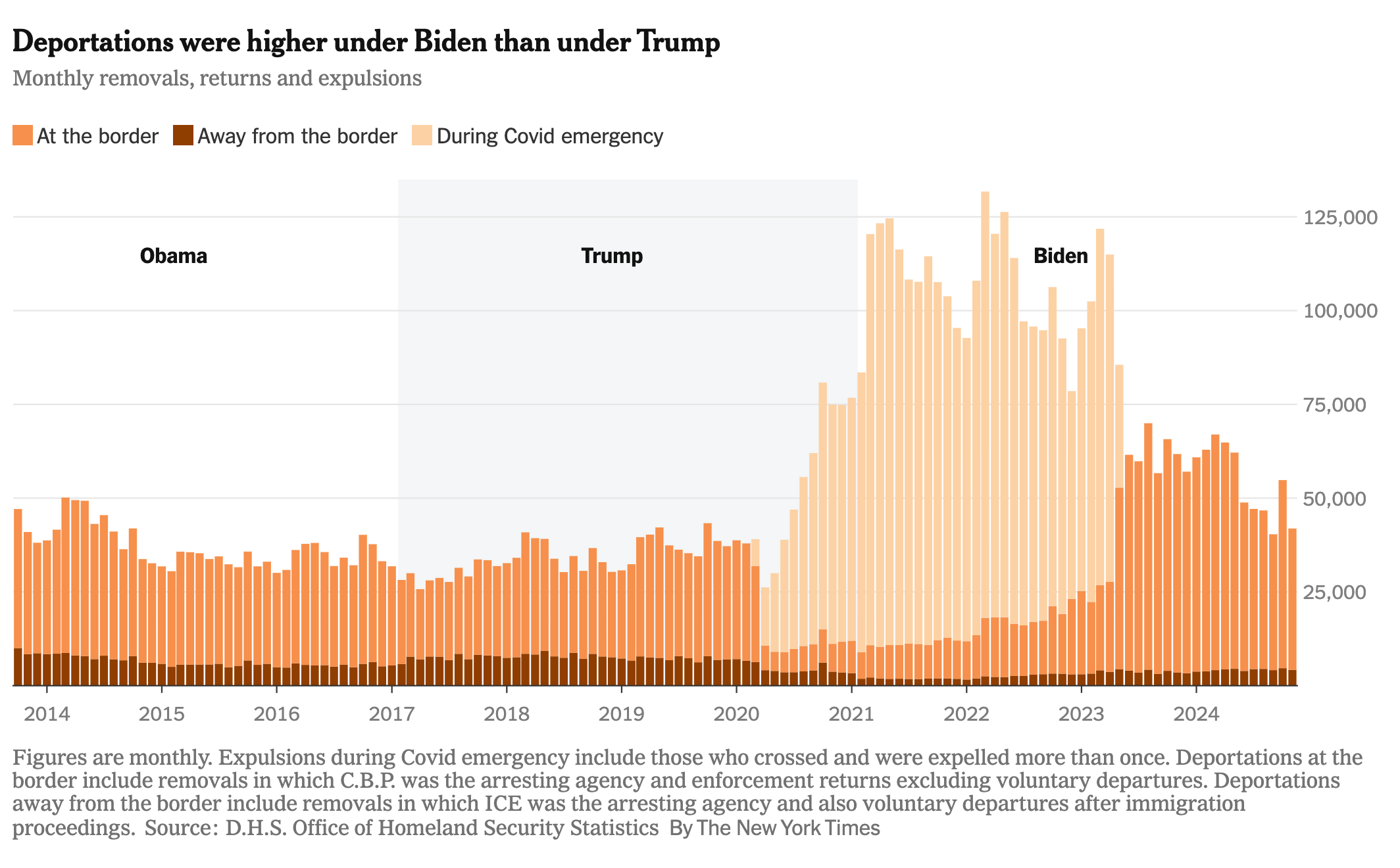

But under Obama or under Biden, things were still very bad. Immigration detention numbers went up. And the very sad part is that the system had already been in place when Trump took over. Obama put in place a lot of the structure for the current immigration detention system. So Trump is really just building on what is already there. And obviously he's doing some very illegal things, but he had a huge head start. I just read something like detention numbers are supposed to triple. But again, all the infrastructure was there for him to do this very fast.

Well, it reminds me a lot of the Patriot Act, how the Patriot Act was this overwhelmingly bipartisan response to 911, and now it's become this template for horrible things the government can do to you.

You spend a lot of time at the Eloy Detention Center. Is there anything else you'd want people to know about what it's like there?

I mean, what we hear, what I hear most from people, is that they're not treated like humans. I just heard that from somebody recently—people who are fleeing their country where they think they could be killed, have also said that they are now worried about dying in detention, especially people with severe medical issues. And people have died in detention. I mean, the medical care is just atrocious.

And food is another thing. We hear all the time that it's food for dogs. So it's just a miserable existence, and people didn't know this was going to happen. They can't believe how terribly they're being treated in the US where they came to seek protection. Yeah, so those are the things I hear most, we're not treated like humans. And the food is for dogs.

Do you have any bright spots, anything that you're really proud of with your work, any success stories or things that you feel good about? I'll put in the transcript, Liz grimaces.

I mean, it's... it's really hard right now. Like, little wins. And I'm also not an attorney, so I'm not specifically working on cases. Some people are winning, which is great. I'm just not necessarily working on that part. And I mean, in the past, we could get people released. We could flag that, hey, this person is seven months pregnant. I think this is in everybody's best interests, including yours, for liability reasons, to let this person out, and that would work. And right now, none of that is working. So right now, it's a little hard to find anything that's like that.

I mean, people are speaking out, that is a bright spot. Media is very invested. There are people who want their story told, there are people who are very bravely coming out and talking about their experiences. So I think that's good that people are paying attention. My hope is that if there is a Democrat in office that will continue.

Whenever there's a Democrat, I feel like there's this whole set of people who just sort of shut it off, and they're like, everything's good, which happened when Biden took office, right?

Yeah. It's done. Oh, the kids aren't in cages. The kids aren't being detained anymore, which is incorrect.

Well that sounds like a really hard job. How do you sort of keep your sanity and not carry it around with you all the time in a ball of rage?

Right now, it's harder, and this probably gets into your other line of questioning about being in community groups that are resisting. I think if that wasn't also going on, I don't know how anyone could do any social justice type work right now. So I think that is pretty much the main thing. I have very supportive co-workers, which always helps. But yeah, just seeing community resistance and organizing is kind of the only hopeful thing.

Groups like Derechos Humanos, for example. So many people came out to resist ICE last Friday only because of that message that there was an ICE raid going on got out to all these different groups. And then dozens of people showed up. So I thought that was pretty amazing.

Yeah, I was really surprised at how fast that happened, it happened over the course of a few hours and there were like 40 or 50 people there.

People brought water, people brought masks, people brought signs. So it was pretty incredible.

Was that the first ICE raid of that sort that you had seen up close like that?

For me, yeah. I've talked to people who were picked up by ICE, just at their house or on their way to work. So it's definitely happening here, but a raid like that, and a response like that, I hadn't seen yet.

What was the most shocking thing about it to you?

I think how the HSI response team, once they got called in, was decked out in all of their weapons. The way they opened the door of their van and piled out like that was incredible. And you can see inside the van, it's just full of weapons, and the fact that they're loaded in that van ready to go and opened it up and then just piled out with all their weapons, immediately shooting at people with pepper bullets, and just doing it so confidently, like they know they're not going to get in trouble, at least right now. Like they know they can act with impunity, and it's just mind boggling.

That was one of the things that really blew my mind with Grijalva, but also just the way they were dealing with everybody was they're so anonymous, and there's so many of them, and they're dressed in this fashion that clearly identifies them as perpetrators of violence, and they really seem invincible. It just seems like these people can do anything they want.

And you know, they can do whatever they want to anybody they want. But the minute somebody even tries to defend themselves against them, you can catch a felony, which is also wild, and it could be for anything. And this has always been the case with the police as well. Not that this happened last week, but with police, spitting near a officer is felony assault, when they can smack you in the face with their baton and pepper spray you in the face. And after the raid, they doubled down on everything that happened. I saw a statement from DHS saying just because you're in Congress doesn't give you the right to approach federal officers.

It's almost like they did that to Grijalva, not in spite of her title, but because of it, almost sending a message that it doesn't matter.

Well, I also don't know if some of those people even listened to anybody. That's the other thing. They don't care. They don't care who you are. They will just shoot at anybody. There was a child there, a little kid, and they just shoot indiscriminately. And I don't even know if they heard her when she said, I am a congresswoman. They just saw her near them, and they shot it at her.

One more thing on immigration, if you had a magic wand where you could change the immigration system however you want, what would you do?

I'm not a great policy person. One very good book that reflects my views, though, is The Case for Open Borders by John Washington, who really explains how open borders are doable. So open borders and zero immigration detention, just no immigration detention at all. And there are different models where people are put in kind of like supportive group homes, but it's not jail.

Interesting how a lot of solutions, when you do it right, look very similar to dealing with homelessness so that's a good opportunity to switch topics. Tell me about how you got involved in mutual aid.

It's a very nice, fluid kind of timeline.

Perfect.

During the pandemic, obviously, I was working from home, and I was also getting very burnt out after working with all my clients with mental health issues, not because of them, but because I could not get them anything. The systems did not work for them, specifically because a lot of them weren't citizens. That goes into a lot of what we see with homelessness—if you're not a citizen, you're a green card holder, but you lose your ID, going through that system to get that back is so hard, but you need to show your work permit to apply for a job. And then if you lose that, you have to go get your work permit again, or your ID, which for a lot of my clients involved going to the consulate and getting a copy of your birth certificate first. It was so many steps.

And then with people who had severe mental illnesses and people who use drugs, they just could not stay in shelters. They were getting kicked out of shelters all the time. I don't know how long I did those cases specifically, maybe eight, seven years, and of the people who were in shelters, I can think of two people who got housing, one through the actual shelter-to-housing system. So only one really.

So I just could not get anything for anyone. And people ended up on the streets, people ended up disappearing, people ended up dying. And I just... there was nothing I could do, especially if they were on drugs.

So I started seeing more about mutual aid and Community Care Tucson, and was thinking, you know, if all of my clients are ending up on the street, then maybe I should just go give them things on the street. Maybe that's the best way. That's when the harm reduction thing clicked for me, and meeting people where they're at. OK, they can't stay in the shelter, at least they can have food and clothes and warm stuff if they're going to be on the street. And I was kind of doing that on my own anyway, providing a lot of my clients backpacks and things like that to help them, or hotel rooms if it was freezing.

So, yeah, Community Care Tucson started, I think it was 2021, during the pandemic. They were functioning for a couple months, and then I went out and helped them a little bit, and then they all got burnt out. So they actually asked if anybody could take over the cooking and the distribution for one week. So me and a couple other people who were newer said that we would try it. So we did, and it was successful. And then I was going ever since then.

I'm always fascinated to hear about what it was like in those early days, when it was organized by teens. So can you talk a little bit about what the distributions were like, especially during the height of the pandemic?

I mean, the distributions were awesome. The people who founded CCT were mostly queer, Indigenous youth. They set up right on the corner of 6th Ave and Congress. So we were in the middle of everybody and everything. The bus station was right there. The Hare Krishna group was always coming down Congress, singing and with instruments. So they would be down the street. It was, like, very beautiful chaos. They had a plastic kiddie pool that they just dumped ice in and dumped all the drinks they had in the pool. They were serving food out of the back of their truck. Half the time, clothes were dumped on a tarp right on the sidewalk on 6th Avenue. Yeah, it was wild. It was very cool.

At one point, I think after they got a citation for serving pizza, they wanted to be even louder, and more like, we're here and we're not leaving. These people need to eat and be protected or taken care of during the pandemic. So they had stilt walkers and a brass band. I always think of it like a circus.

CCT eventually moved to Armory Park, but what else has changed since you've been involved?

There's obviously more people, more people are serving and more people who are volunteering, but there's more people involved in, I don't want to say running the group, but more involved in the logistics of the group. So there were just a few people who would go and buy all of the food and hygiene, whereas now we have a couple people who are buying the hygiene, a couple people who are buying harm reduction. And it takes a lot of work and pressure off when it's not just one person doing the shopping. I was volunteering to do that for a while, and it was really difficult to go buy all of the food and the drinks, and even just to push the heavy cart through the parking lot to my car.

I think even when I started, it definitely felt like everyone had to go every time. Whereas now I feel like you can miss a week pretty easily, and there's 20 other people there to do the work.

What is something that you would want people to know about the people who we work with in the park, neighbors who show up, whether it's unhoused people or otherwise?

I think in the five years or so that I've been out there—and we see people who are using drugs, who have a mental illness, who show up drunk—I don't think I have ever once felt like there has been an actual dangerous situation. Despite seeing thousands of people at this point. I mean, obviously that has taken some work. We talk about these things a lot, how to deescalate and what happens if the situation arises. But we've been able to, if not defuse every situation, I still have never felt like anybody was in danger, or like anybody that we serve was going to do us harm. Which I think is a very big thing that you see in the media a lot is you only see stories about unhoused people who are harming others. But yeah, in five years, and at my job, actually, running around with people and being in the park with thousands of people, I've never once felt like I was in danger.

I mean, the only thing that I would maybe say is that I have felt somewhat in danger when police are there. Police are the only time where I've ever felt like, oh shit. And also, I've noticed, whenever police are there, that's when other people at the park start to have aggressive responses. It's amazing how, whenever there's cops in the park, the tone just changes. People are on edge.

I also feel like the more people we've had at the park, the safer it's felt. I think some people might think that when you get a huge crowd of people, it becomes more dangerous. But as we've grown, I feel like there are few situations we couldn't deal with, just because we have such big numbers.

Yeah, and I think a lot of the people there who we serve also would help us in any of those situations, because again, we're out there meeting people where they're at. And we're friends with a lot of them, so they will also try and defuse situations to make sure everybody is safe and the park is safe and the distribution is safe.

Is there something that stands out that you're really proud of from working with CCT?

I think there's a lot. You know, we kind of adapt to what people need and we're not stuck in a mode of, we give out this, this, this, and this and that's our role. For example, there's a couple people who are housed who need more food, or who are sick and need medical supplies, and then we try to get that for those people. A young family needed diapers and wipes, because they're so expensive right now, so we were able to get those for those folks.

And also just using the community resources that we have, posting on social media or working with other groups. I think it's great. And literally furnishing people's apartments, because that's something that always blows my mind. People getting apartments, through the city or through a program, and they're not furnished, is just mind blowing to me. You know, people getting into housing, then when you look at the apartment, they have nothing.

I've talked to people who get into housing and they're always very happy on one level, but it can also be difficult. If you just go into this empty room, it's a very different environment than when you're living in, say, a camp.

I think this is one of the main issues with Housing First. And I know a lot of people would probably be critical of this opinion, or the opinion of somebody that doesn't like their apartment, that they should just be thankful that they have it. But again, I think a lot of Housing First is still kind of making someone conform to what we think their life should be.

I remember one person who got an apartment that was like 20 minutes across town from where he was staying, and he hated it, because he was so depressed. Before, he was always with his community, and then he was waking up alone in an apartment and was traveling so long to go back to his community. I think Housing First is great and works for a lot of people, but there are other models, like group homes and things that are much more community based. I mean, some of these programs are very individualistic. Housing First is like, you now are independent. Like, the whole point is to get people to be independent and a working member of society.

Which we all know there are many people where that's not an option, that's not realistic.

So if there's other supportive models, like a group home... You know, I always think that people would go wild if we used tax money for more supportive group homes where people were getting their meals for free, three times a day. But that is what we are paying for with a jail. We are paying for free housing and three meals a day. Why not pay for that, but for actual nice homes?

I worked with one person who was mentally ill, really, really sad, young guy, he was like, 30 and he had been getting charges since he was 17. Because of mental illness, schizophrenia, he started using drugs, and then started just racking up, probably, like, I don't know, four charges a week. I mean, he's pushing hundreds of charges. A lot of them got dropped because they were bullshit.

But he was put in a group home with four or five other people. He had his own room and own bathroom. And 24/7 support, again, this was just like a small place. It wasn't a locked facility, it was very homey. They cooked for them, and they helped him get a job, which he actually did. They took him to and from his job every day, gave him a bagged lunch. He was there for a year. During that entire year, he never used drugs, and he didn't get one charge. They put him in an apartment by himself, and after that, he was back in jail within a couple months. Why can't there be that kind of support permanently for people who need it?

The thing with Housing First that you mentioned that I think was really true, is that it is very much an individualistic approach to think that once you have property and possessions your problems will be solved. And that sort of model of success can be very isolating.

I never want to glamorize homelessness or what it's like living in camps, but also, these communities are often creating something that society was not giving them.

And that's why a lot of people don't want to go to shelters too. I mean, why would they want to go by themselves, only take some of their belongings, and then leave the community where they're cooking together and sleeping near each other. Then you go to a shelter where there's 60 other people in the room. You don't know who they are. Have probably been burned before in the past for people stealing your stuff, and then all of a sudden, you're on edge again, even though being in a shelter is supposed to fix things.

We hear from people who are like, I'll never go back to that.

So I really would just like to try and keep building on providing people with what they say they need, what their basic needs are, so we don't become stagnant. One really cool thing that Just Communities Arizona is doing is installing Porta Potties. Because one of the main things we hear is people need bathrooms. So being able to buy a bathroom trailer, or a shower trailer, and telling the city, suck it, we're gonna do it.

And one other thing I wanted to do for a long time is have a place where people can do their laundry for free. I remember this couple bought a laundromat and essentially turned it into a day center. Kids were coming there and doing their homework. The laundromat is often such an important place for community. It could be transformed into a really good community center.

This is a hard question. But we talk lot in Community Care Tucson about how mutual aid is actually trying to change the world, and not just be a band-aid on things. How do you envision mutual aid actually making the world, on a larger level, be a better place?

Yeah, that's very difficult, because I'd love for us not to be necessary, but it seems like mutual aid always will be necessary. And on the other hand, it should be, because it's all about community care. So I don't know, it's very hard question.

I think community by community, town by town, neighborhood by neighborhood, it's about being able to at least educate people and show people that everybody is deserving of the same type of humanity and dignity. And again, I think a lot of it is meeting people where they're at, so not forcing people into whatever model we think should work. We always come up with all these models and systems like this is going to be the one to solve everything. But obviously, everybody is different. Everybody has different wants and needs. So being able to meet those wants and needs outside of just a one-size-fits-all model.

I know we're going a little long, but I wanted to give you a chance to complain about the city, and we haven't gotten there yet. So a lot of horrible things have been coming out of the mayor's office and the city council since we've been doing this work, including routine sweeps and multiple mass arrests. What do you find most frustrating about the way the City of Tucson is dealing with social problems in the city?

Yeah. So first of all, I think that our city, and several of the elected officials, are very good at manipulating language and manipulating the narrative. So a lot of the things that they're doing, like the "safe city deployments" sound very similar to what Trump is doing in DC, but they get around that by throwing in words like "social service agencies," like, oh, a social service agency is coming out with us with so it's OK.

And just how vague they are with their language when they're talking about these things, like "services are being offered." They don't have to give any specifics. And we often know that is just a pamphlet, like we saw a pamphlet once of what was given out during a sweep of unhoused people, and half of the page was about rental assistance. And that's how they're saying that this is okay and this is progressive because they're doing it with social service agencies, or because they're offering resources.

Resources that are often worthless to the people they're dealing with.

So the fact that they can get away with that, just being so vague, manipulating language and manipulating the narrative, when really a lot of the things they're doing are very backwards compared to what we know works.

Like with the drug ordinance that they're thinking about passing, Kasmar, the chief of police, implied that when people go to jail, they reflect on their lives and change. This is common knowledge at this point that that doesn't work, that's not true — and nobody spoke up. None of the elected officials challenged that. It's wild.

But again, our city can frame these approaches as progressive, and then when they fail, that gives people like conservatives the ammunition to then say, oh look, these progressive policies don't work. When they weren't actually progressive in the first place. They've never actually done real progressive models, like overdose prevention sites, needle disposals, Narcan vending machines.

And second, I've been hearing this a lot, especially with the drug ordinance that essentially gives police the ability, not that they don't already do this, but on the books, gives them the ability to just approach somebody who they think looks like they're going to use drugs, or they know that they use drugs, or they know that they used drugs in the past, not even to search them, but to arrest them, for nothing.

I've heard a lot of elected officials saying, you know, we just need this to appease NIMBYs so we don't get sued, or whatever, but it's not really going to be enforced. But we know that there are those police officers who will take that and run with it. And we've seen it on video.

In reality, it is going to increase the criminalization and dehumanization of people. And I feel like we use those words a lot, but I think what we're hearing from people in the park is that they think the city hates them. They think the city wants them to die. They think the police hate them. They feel less than human. They're treated less than human, and they're exhausted.

Well, it's similar what we were talking about with the immigration laws and the Patriot Act, where Democrats will say we need this tool and we can use it judiciously. But then, once the tool of power is in place, anybody can pick it up, right? Romero sucks, but imagine if somebody worse than Romero came in and had these tools in their tool belt.

And it's like the ordinance for the permits for who can get food and water at what time and where. You really want that on the books? That the government can decide who gets food and water and when and where?

Is there anything related to other social movements in Tucson that you've been really proud of, whether it's things that you've worked on, like maybe the jail fight?

The jail win was great, yeah. I don't know, I just think in Tucson, what we've been building over the past five years with trying to not silo these different issues has been amazing, like partnering with Reconciliacion en el Rio and Angel on water justice issues. They were huge in the jail fight, saying you can't have a polluting jail on the Santa Cruz River.

And right now we're talking a lot to folks in the Stop the Kidnappings campaign. We have been seeing the increase in criminalization of unhoused people by the police, so I was talking to them about how all these branches work together. Because there's a lot of unhoused folks who are immigrants, and the more that you police people, the more flags for ICE there's going to be.

So all these groups working together and seeing how all of these systems contribute to fascism and imperialism, and then joining forces to advocate and stand up to these different agencies. They're all connected. So really, it's everybody's fight. All these fights are everybody's fights. So I think that's been a huge, huge thing in Tucson over the last five years that we've built.

Okay, a soft question. What do you love about living in Tucson?

I mean, this is kind of like what I just said, but I think the connectedness, the small town feel, and the connectedness among different groups and also different local businesses that help us a lot. I've had people come up to me and say oh, I've never seen so many businesses supporting mutual aid in my city. So just the fact that we can go to these local businesses and know that they're our people is amazing. And then you see just people from different groups and different businesses, all over, doing different things. You just see people everywhere, which I think is very cool. It feels very community oriented.

Okay, last thing, when I was watching that raid last week, seeing the clips of it, it feels very disempowering. So I guess if people are struggling with this feeling like they are helpless or powerless, what do you recommend they do?

I mean, that raid was really bad. But there are groups specifically here that you can get involved in like Red De DefensAZ, which is trying to help families in Tucson who have people who are detained, and they are trying to help them with their basic needs, with legal services, with community, with support. Derechos Humanos also has working groups organizing political things, but some of their working groups are just childcare. Some of their working groups are emotional support for people who are struggling. That's maybe not going to break the system, but that's super important.

And I always say this to everyone, even when I'm doing presentations at work. I always am like, join a mutual care community group.

That's good advice. Alright, that's all I got. Thanks Liz.

OK this was a long one, so going to wrap it up. Stay tuned for more conversations with people doing cool things. And you can read some other past interviews here:

Every city is a war, a conversation with author Sam J. Miller

Poetry as resistance, a conversation with poet Tamiko Beyer

Inalienable, a conversation with author Cadwell Turnbull

Until next time, unclench your jaw, take some deep breaths, touch dirt.

Tate