98: Rewriting our own story

Ministry for the Future tells the greatest story of our time, brilliantly, and with no resolution

--

For years, there was this common refrain in the news media but also regarding books, movies, etc., that climate change is just not a topic conducive to broadly accessible stories. Chris Hayes notoriously once said that talking about climate change on his show is a "palpable ratings killer." It's too slow and spread out over time, there are no clear heroes and villains, it's too technical, it's boring, nobody wants to read about it.

This is, of course, not actually true, and the success of a book like Kim Stanley Robinson's Ministry for the Future strikes me as proof that climate is actually a topic overflowing with compelling stories. The opening in particular is so gripping that it makes you wonder why we haven't books like this for years. It's hard to say exactly why there have been so few breakthrough novels and short stories about climate change. There are actually a lot of them, several of which I have read and liked quite a lot, but not many have made it into the mainstream (Robinson himself has been writing about climate change for some time, including 2312 and New York 2140). So maybe there is some truth to the claim that audiences weren't ready to confront it head on, or maybe it's that not enough writers were ready. That would explain the steady flow of fiction that is not literally about climate change, but I would argue is actually about climate change in tone and theme (the surge of apocalyptic horror comes to mind).

I think there's also some truth to the claim that climate change is not an easy story to tell. Other writers have certainly done so successfully, but Ministry for the Future is what I tend to think of as the first big swing that an author has taken at writing a climate change masterpiece. Big and all-encompassing, it is clearly the work of a writer who is willing to take on a huge topic, and trying hard to get his brain around the entire thing. It is perhaps too big a swing, in fact, as some will no doubt find the page count daunting. But I think that too is a deliberate decision to honor the subject with the depth it deserves. Because of that ambition alone, but also its overwhelming success in execution, I think Ministry for the Future is a not just great book, but an important book that I would recommend to anyone.

It's ambitious in scope, but also in its form, and I think that's a key ingredient to the book's success. Because climate change is a topic that tends to unravel norms and standards we are accustomed to, it strikes me that writing a great climate change book requires the novelist to toss aside many of the frequently used tools, or at least push them to their limits. So there are many common fictional tropes here, but they are chopped up, stretched out, sometimes left behind in the dust and debris. They are also punctuated by less conventional containers for Robinson's ideas, whether that's an imaginary talk show, meeting notes, poems, riddles, or explanatory essays.

That makes for a meandering narrative, but one that moves quickly and is teeming with ideas and imagination. A bit like the essay collection All We Can Save, instead of attempting one singular, linear argument, the book builds a kind of ecosystem of ideas, each of which offers a new potential point of entry for readers. The result is as thought-provoking as it is emotional, stirring up a mix of enthusiasm, depression, distaste, and grief, as any examination of climate change should.

Optimistic, sort of

Ministry is a science fiction book, but it's not exactly a science fiction book, a distinction I make with reluctance as someone who loves science fiction but understands that not everyone does. I don't want to denigrate the genre, but it's one of those books that sci-fi readers will enjoy, and skeptics shouldn't be afraid of.

It takes place in a world that will look very familiar, but teased out into the future just far enough (2020s-2040s) that Robinson can deconstruct reality to his liking. This is a tried and true sci-fi technique of using an imagined future to better critique the present, allowing us to reevaluate our world and our lives in a way that won't feel like an attack or a manifesto. But it's also quite literally a book about what the future might hold.

It's largely optimistic, although that feels kind of weird to say considering [spoiler] at least many millions of people die, main characters suffer greatly, some are killed, and others are imprisoned for the bulk of the book. But in a societal sense, it asks the question of what the world might look like if society were to actually make radical changes in the face of climate change, sometimes voluntarily and sometimes not. What would it take for us to survive an inescapable worldwide crisis, and then keep going?

And the answer is, often it looks pretty shitty. But other times it looks spectacular. Sometimes it's a ride on a giant dirigible, sometimes it's a terrorist attack. And sometimes it's just a peaceful afternoon on a hike with a friend. Because that's what living through a global crisis is actually like. Ups and downs. But it's optimistic in the sense that it is a vision of humanity doing big things, breaking and building, rewriting our own story.

A book of ideas

Setting aside the story for a minute, many people will say in either positive or negative critiques, that Ministry for the Future is primarily a book of ideas. That's fair, and specifically, it is a book of ideas about how far we would or could or should go in order to continue as a species. Robinson is clearly such an incredibly smart and well-read person, and a lot of this book is him getting all of his dizzying ideas about what could happen in the coming years down on the page.

As a result, it is much less a book about science than I anticipated going into it. I would say much if not most of the book's speculative elements involve economics, governance, even religion, as opposed to geology or chemistry. So maybe it should be more accurately described as social-science fiction, in which the author's imagination is applied to societal innovations we might concoct. Every decision we could make as a collective is written as a kind of invention that we might put to use—a solar-powered clipper ship is as much a needed innovation as a new kind of currency or worker cooperative. In one of the book's discursive chapters, an imaginary debate about technology concludes:

By that line of reasoning, you end up saying design is technology, law is technology, language is technology— even thinking is technology! At which point, QED—you’ve proved technology drives history, by defining everything we do as a technology.

But maybe it is! Maybe we need to remember that, and think about what technologies we want to develop and put to use.

Some of my favorite moments in the book are these sections that are framed as arguments between two nameless, faceless people, in the form of some kind of talk show or debate. I kind of think of them as Robinson debating with his own mind, as we all do, or as a debate between optimism and pessimism, or change and the status quo. Other sections are framed as encyclopedia entries, or persuasive or informational essays.

Many of these ideas are not even that speculative, if at all, reflecting concepts from actual academic papers or fledgling features of our current reality. In that sense, it functions like a synthesis of our current knowledge of the climate problem and its possible solutions, in fiction form. So you might read a chapter and think, oh yeah, I remember that article, except it's been brought to life in a fictional setting.

It's also worth noting that the book is told unapologetically from a certain ideological perspective, and I'm guessing Robinson would not argue with this. Ministry is highly critical of the havoc global capitalism has wrought, and a pretty clear proponent of democratic socialism or at least social democracy. But Robinson is not dogmatic in his beliefs, and spends a lot of the book considering how markets can be put to better use. You get the sense that he feels the delineations that define our current political debates will mostly wear out their usefulness amid climate catastrophe.

If anything, he's using the novel to put his opinions to a kind of stress test, smashing them up against unthinkable barriers and conflicting outlooks to see how they hold up. And in all cases, the underlying message is that the assumptions we currently cling to about the way the world works are nothing more than assumptions, and can be reimagined wherever we have sufficient will.

Denying us a neat sense of closure

In a similar way, the book runs up and down societal strata in a way that I did not anticipate. My biggest fear about the book—coming from a genre that at its worst is about white dudes doing science and computer stuff—was that it would be mainly a story of technocrats and experts bending the environment to their will. There is some of that, with several geoengineering plotlines, which are a lot of fun in the spirit of what if we just said fuck it and did this. There's a surprising amount of attention paid to blockchain. The main character is essentially a diplomat, and the titular institution a bureaucracy. But neither stays within those definitions, because the situation demands they break out of them.

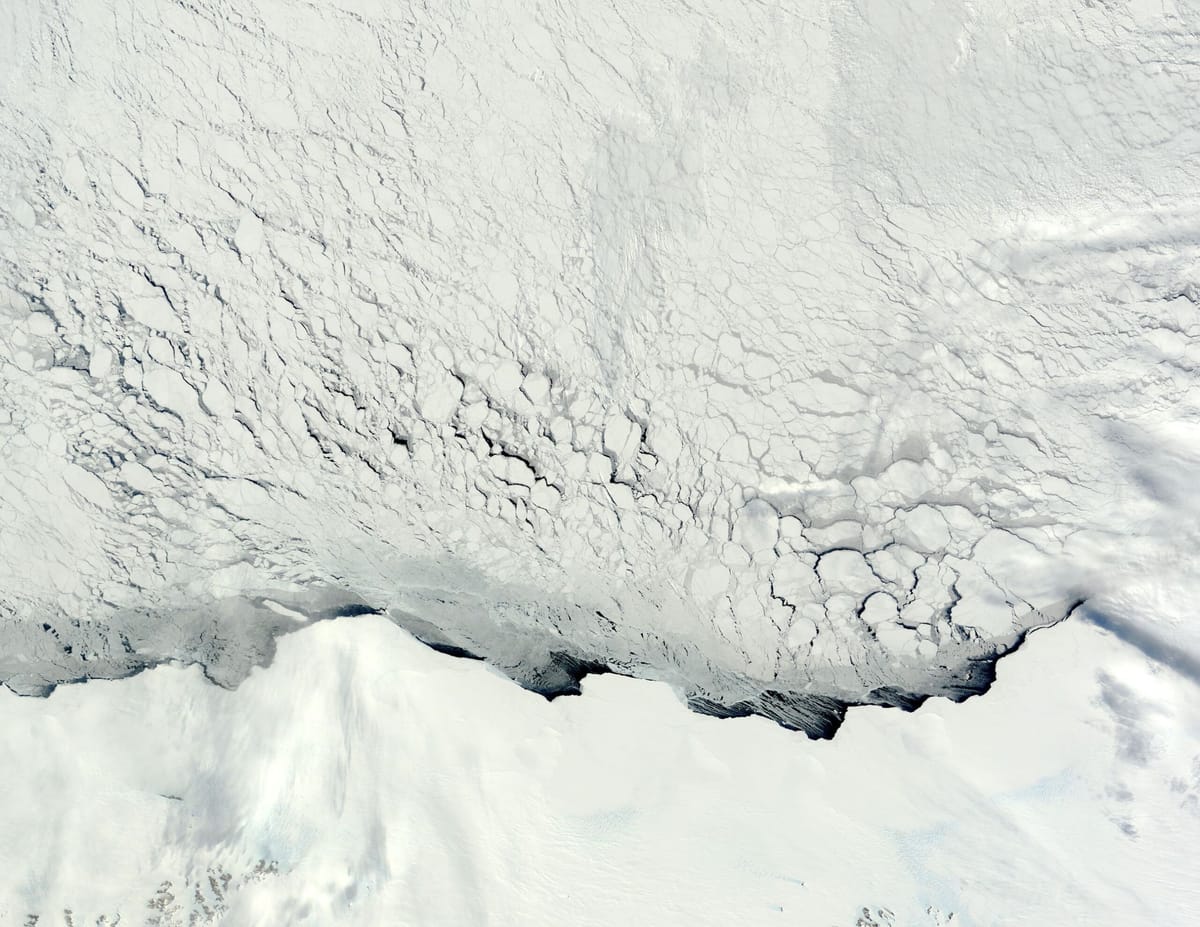

The narrative, too, breaks out of the initial bounds that it sets for itself. The book's sort of homebase is Switzerland, and the biggest criticism I have is that more time could have been spent among communities impacted the most and less time could have been spent in Europe. But the action of the novel jumps all over the place, to India, Los Angeles, the rural Midwest, Antarctica, China, and many more locations. At times, it feels like a spy thriller, but just as quickly abandons the genre for an uneventful day in the park. At various times, our heroes are bankers, protestors, NGO workers, farmers, kidnappers and saboteurs.

As a result, mileage will vary with certain threads of the book. I found myself at times thinking, ah man, back in Geneva really. It has a few cheeseball moments too. But it's never slow, moving along at a rhythm that is fast, but willing to give you a beat between the really heavy moments. Again, it's not unlike the way All We Can Save uses poetry and sequential art to provide the reader with some time to breathe.

Another downside to this format is that there are plotlines that begin and just trail off, in ways that deny you a sense of neat closure. But again I think this serves a purpose. If Robinson shares my frustration at the lack of popular climate storytelling, the many unfinished mini-novels that populate Ministry could be seen as invitations for all the climate books that haven't been written yet. I'm eager to read the full stories of (mild spoilers) the failed actor kayaking through a flooded Los Angeles, the great heatwave of the Southwest, the rewilding of Midwestern farmland, the nonviolent occupation of Paris, the NGO worker gone rogue, the premeditated murder of Facebook.

This wandering abandonment of narrative arcs might feel like a failure to some readers, and it can be frustrating at times, but I suspect it's done intentionally. As much as Ministry for the Future challenges our ideas, our assumptions, the costs we are willing to accept, it also challenges what we should expect from a story about a topic that holds no singular message. Instead of a linear storyline, it's an emergent one, putting human narratives within a jarring progression of time, picking up and putting down characters as the winds change. It's more like a flurry of developments that continue until, before you know it, it's a very different book than the one we started with.

Instead of a climactic resolution, it's a diffuse one, not really an ending at all. In the final scene, characters look at a statue of Ganymede and Zeus, struggling to figure out what it's trying to communicate. "It has to mean something," one says. "Does it?" the other replies. "I think it does."

It's a not-so-subtle commentary on the vision that Kim Stanley Robinson himself has put forth in this book. That we're not going to walk away from this with a sense of resolution or victory or a moral of the story. But it's still an inspiring, important story, the story of humanity itself, and it's one we can't be afraid to tell.

--

Links

- I will spare you any articles on what is happening in Congress right now but in case you missed it, it fuckin sucks!

- More than half of police killings are mislabeled, raising huge questions about how much of a threat police actually pose to society and also about racial bias among medical examiners.

- Kids will live through three times as many climate disasters as their grandparents, but in some places it is much worse. "Infants in sub-Saharan Africa are projected to live through 50 to 54 times as many heat waves as someone born in the preindustrial era."

- The Canadian Rockies are very beautiful and they have these glowing turquoise lakes that are losing their color because of climate change.

- Cities are testing guaranteed income for artists.

- Republicans and industry are using a legislative tactic called "preemption" to make it illegal for cities to pass laws that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The tobacco industry infamously used the same technique in the 90s to dodge wrongful death lawsuits.

- OK I lied here is one article on Kyrsten Sinema, who is building her career on being a political independent, which means refusing to vote with her party for no clear reason, refusing to say what she would vote for, changing position at the behest of corporate lobbyists, and making everyone all around hate her guts. The ending says it all about just how independent AZ voters really are: "would Ms. Odell actually vote for Ms. Sinema or anyone with a D beside their name? Probably not, she said."

- Extinction Rebellion blocked the entrance to Charlie Baker's house with big sailboat and chained themselves to it. (They edited it but at first this article used the term "climate control activists" which I thought was funny and weird.)

- Boston is one of the wealthiest cities in the country we are literally building half a dozen new skyscrapers and entire new neighborhoods for rich people, but our public transit system is falling apart to the point that it is a deathtrap.

- Yes this mosquito season was worse than normal and yes it's because of climate change.

- The guitarist from Pearl Jam has paid for or helped pay for 27 skate parks in Montana, and three on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

--

Listening

I like this LCD cover by Ezra Furman which I first heard on the show Sex Education, which I also like!

--

Watching

I read Y: the Last Man comics as they came out issue by issue back in the old days you know the old fashioned way and I've been mostly enjoying the TV adaptation. Speaking of Boston being a deathtrap, I was honestly a little flattered that in a recent episode it was portrayed as the one city in the country that had descended into complete rebellion. Some TV writer clearly went to college here and has opinions. Here are some of the Boston moments I enjoyed the most. It was not filmed here, but this is supposed to be Fenway:

--

OK that is all for this week. Speaking of Fenway last weekend we went to a Red Sox game with my father-in-law Jimmy and it was a blast it was like we went to church with him. The Red Sox lost but it was still a great time and perfect weather. Here is a fun fact one time we went to a Red Sox game and you can do this fun thing where you ask the organist this awesome guy Josh Kantor to play a song and he will sometimes do it, and Jamie asked him to play a Tori Amos song and he did.

This newsletter is like my own little Tori Amos song played for you, except instead of an organ I am using Wordpress. But the love I put into it is basically the same.

Tate