87: No hero 2

Because what's a superhero story without a sequel

Tiger in a Tropical Storm, Henri Rousseau, 1891

--

A few weeks ago I talked about the perils of America's fixation with fictional and real-life superheroes, this class of people who stand above the rest, acting with impunity and admiration and almost always in the defense of the status quo.

The title of that issue was No Hero, which was a reference to a dark indie comic of the same name by Warren Ellis and Juan Jose Ryp, about a group of radical superheroes called The Levellers, who formed in Haight Ashbury in 1966 and gained their powers by taking drugs. Their first act in the comic, which was published in 2008, is to stomp a bunch of San Francisco police who are attacking a kid because he stole a can of paint. Of course, as you might imagine, The Levellers eventually go horribly wrong, morphing into a kind of deformed world police force themselves, called The Front Line, and misery and chaos ensues.

I was going to write about Warren Ellis in that earlier issue so that's why I named it No Hero, but I didn't have enough time and also writing about the sexual misconduct scandal of a British comic book writer seemed a little far afield. I kept the title because it sounded good. But you know what, I'm going to go ahead and write about it now, because it is timely again and it is my newsletter and because Ellis's fall and the recent faint pulse of his redemption has been informing a lot of my thinking lately about our relationship with heroes, and how we can hold them and ourselves accountable when they inevitably let us down.

So bear with me and even if you have no interest in comics, I'm sure you can just mentally swap in the name of someone you admired who did something terrible and you've had a hard time coming to terms with it. You know you have one in mind. And as always it will become relevant to bigger stuff so sit tight.

A good chunk of Ellis's work is cut from similar cloth as No Hero, and he's maybe best known for a series called The Authority, in which a group of superheroes get fed up with the state of the world and decide to turn against the corporate and political powers that be (the opposite of the kind of tool-of-the-state superhero story Ted Chiang was lamenting). But I first began to really love Ellis's work when, as a college journalist in the 90s, I read Transmetropolitan, a book about a gonzo reporter in a dystopian future America who takes down crooked presidents, his only weapons a newspaper column and a bowel disruptor gun that well you can probably figure out what it does. It's a deranged, technicolor, ultimately deeply moral story and ever since I found it, I've read just about everything Ellis has done and loved most of it.

Every now and then you find a writer who for whatever reason their perspective just clicks with you. For me, a lot of that is his sense of humor and staggering talent for gathering up and sharing cool ideas. But like a lot of my favorite genre fiction writers, much of his work is ultimately about power. What it takes to acquire it and what it takes to tear it down.

The other thing to know about Warren Ellis is that over the years, he developed a somewhat ironic, but also kind of not at all ironic, cult-like internet following, especially in the Wild West days of early 2000s web. He was always starting new email newsletters, message boards, webcomics, blogs, websites, and every time he did, a thriving online colony of creative counterculture types would follow in swarms.

I never got very deep into the forums, just an occasional lurker, but I did always subscribe to his newsletters and for years his weekly email was the one I always looked forward to the most. Because of this, his fans really feel like they know him personally, and to some extent they do. His work and his persona fused together over the years, and often his weekly online bulletins were as rewarding as whatever he was publishing at the time.

With all of this, Ellis accumulated a certain amount of power himself, at least in certain circles. And it was generally perceived that he used it for good. He developed a reputation for helping out young artists and writers, particularly women coming up in a male-dominated art form. A good number of today's leaders in the field got there in part because of Warren's help, including Kelly Sue DeConnick, who became a prominent figure in mainstream comics and championed feminist storylines within a genre steeped in toxic masculinity—she created the basis for the MCU version of Captain Marvel. (DeConnick met her now husband, another esteemed comics writer Matt Fraction, in a Warren Ellis online forum.)

Ellis also became known as an online figure who never suffered fools. He never minced words, and his online communities had strict rules that booted anyone displaying misogyny, harassment, or other bad behavior. There are stories of men being sexist or abusive and Warren would more or less publicly thrash them and ban them for life.

But, and you probably saw this coming, it turned out there was a very dark side to all of this that people were aware or unaware of to varying degrees. About a year ago, a flood of accounts of sexual misconduct by Ellis emerged, eventually documented on a website called So Many of Us. It came out that Ellis had been cultivating sexual relationships online with fans and proteges, as many as 20 at a time for a while, grooming young women in very similar ways in each case, and eventually ghosting them when it suited him. It's similar to the kind of abuse of power we've now seen from so many men in creative fields, using their position in the industry to manipulate people who admired and trusted them. It sent a shockwave through the comics community, prompting long overdue conversations about toxic environments and gatekeeping.

I first heard about this when I got an email from Ellis, but this one at a weird time, a random weekday afternoon. And it was nothing like his other emails. I would be surprised if it was written by him, as it was a stilted, tone deaf, lawyer-up-style non-apology. One last betrayal in the form of a bunch of bullshit, the one thing you thought Warren Ellis would never subject you to. It's hard to describe just how upsetting and infuriating it was, and I hesitate to try, knowing that what I had to contend with was one-one-millionth of what the dozens of women and non-binary people he mistreated had to go through. And yet here I am, a dude on the very distant outskirts of the shockwave of hurt this guy created. I spent that Saturday reading through many of the testimonials, of which there are now 37 online (over 60 signatories overall), feeling an unshakeable queasiness at the similarities across their stories.

It was like finding out someone I knew and trusted, like a admired relative or teacher, was in fact not a person but an alligator or a rhinoceros. An entirely different kind of creature than what you thought. But he isn't that of course. He's just a person, an insecure man in a position of power. Not a hero and certainly not a superhero. Another reminder that, even in groups on the margins, even in circles of people railing against power in their own way, there will always be men who do awful things.

And that leaves us with the terrible question. What do we do with these people, not always (JK Rowling) but let's face it almost always men, who we once looked up to but have let us down? It's something I've been thinking a lot about in the year since, but I guess, really, since November 2016. It's the question underlying my earlier email, and its conclusion that we should challenge the way we valorize our billionaires, our politicians, the people we too often expect will show us the way or save us from ourselves. We might also apply that same precautionary principle to our sense of fandom or intellectual admiration.

Sometimes the answer is easy just goodbye move on. But sometimes it's not so easy. The discourse would have us believe that there are only two ways to handle the problem. The first is the much-feared, mostly mythological cancellation—the removal of the person and their work from the public sphere. The second is giving the proverbial pass, under the banner of "separating the art from the artist." The idea that well, nobody is perfect, we can't demand moral purity from creative people, therefore we should just tolerate the pain they've caused others as the price of a good movie or book or whatever. Most of us, I suspect, end up stuck somewhere in between.

In 2017, Amanda Hess wrote one of the best essays I've read on this topic, titled, "How the Myth of the Artistic Genius Excuses the Abuse of Women." "Can we now do away with the idea of 'separating the art from the artist'?" she asks, arguing that it's the very elevation of these men as something special, this creative class separate from the rest of us, that allows them to harm other people (often destroying other people's equally valid art) and then insulates them from consequences. She challenges the taboo commonly enforced by male critics that says we must never consider an artist's work in the context of their lives and misdeeds. More often than not, however, the deeds of the artist live and breathe in their work and cannot in good faith be ignored. She writes:

It seems uncontroversial that offenders who remain in positions of power ought to be unseated to prevent further abuses. As for the art, we can begin to consider how the work is made in our assessment of it. This conversation is often framed, unhelpfully, as an either-or: Whose work do we support, and whose do we discard forever? ...

Drawing connections between art and abuse can actually help us see the works more clearly, to understand them in all of their complexity, and to connect them to our real lives and experiences — even if those experiences are negative. ... If a piece of art is truly spoiled by an understanding of the conditions under which it is made, then perhaps the artist was not quite as exceptional as we had thought.

I would add that it also seems uncontroversial to stop giving our money to offenders, but I think Hess's suggestion that we intentionally conflate the art with the artist is a useful one, as a means of removing them from their pedestal. Sometimes, as Hess suggests, this will reveal the emptiness of the art (Ryan Adams comes to mind). Other times it might change the way we interact with certain art or ideas. But, critically, this does not mean absolving people of what they've done. We hold people accountable, feel the anger and betrayal, and then we sit with it. With all of it.

There's another important benefit to this approach, which is, if we allow ourselves to look head on at the entire picture, instead of closing one eye or turning away when we don't like what we see, we leave a door open for repair—and maybe even forgiveness.

When the people who publicized their accounts of Ellis's abuses came forward, one thing they made clear is that this wasn't meant as a campaign to take him down. Instead, they invited him to take part in a process of "openness, accountability, and growth, extending an offer of working with Ellis on some form of transformative justice."

At the time, he ignored the invitation and basically dodged any responsibility. But recently, upon some unexpected news that he would be returning to comics, the backlash started up again, almost as intense. And so, I got another email, the first one in a year. And this one was a little better. Longer, sounded more like him. And it started by saying he's been silent for too long and he has accepted the invitation to be part of a mediated dialogue. People will say that he only did it when he basically had no other options, that he was forced, and it certainly looks that way. But I don't know that I really care either way. Ellis has got a long way to go before many people, myself included, will be ready to forgive him, but maybe it's a start.

For a long time, I've had a kind of "special bookshelf" that holds like a half dozen of the books that I go back to over and over again. Some of Ellis's books were on that shelf, but last year I took them down. I didn't throw all my Warren Ellis books in the trash, but I did put them on a regular old shelf with all the rest of my books. That special shelf was starting to feel too much like a pedestal, and it's one I'm not sure I want to have anymore.

I like to think that we're going through a period of accelerated change and heightened accountability, whether that's related to police brutality, sexual abuse, structural racism, misogyny, abuse of each other, abuse of the land, abuse of entire cultures. Some of that greater accountability is a result of hard fought progress, changing the norms of what we are willing to tolerate. Some of it because we've simply reached a point where people who have spent generations taking and taking now have a bill to pay in money or blood, through flood or fire.

With that change will come this recurring question of who caused harm, who must be held accountable, and how much we can forgive. Sometimes the subject will be a clear villain. But other times it will be people once held in high esteem or people we maybe even thought of as heroes. I think we're capable of a lot of forgiveness, but that's not possible without a truthful accounting of what damage has been done, and the only way to get a proper look is by bringing them down from that special shelf, down here with the rest of us.

--

Links

- The West is bracing for "a heat wave for the ages that could absolutely destroy all-time records from Washington to California as well as parts of Canada."

- Much of the Southwest is in a "megadrought" which is the "driest 20 year period since the last megadrought in the late 1500s, and the second-driest since the 800s."

- Heat islands in Boston are cooking lower-income neighborhoods, sometimes as a result of poorly planned city projects. The difference in temperature can be as much as 10 degrees.

- I like how the pandemic caused this spiritual awakening in which people realize they don't want to waste their lives in horrible jobs and the discourse is basically "this could be bad for inflation how can we get people to go back to their horrible jobs."

- People are wilding out on South Boston's beaches, including roving packs of marijuana smoking teens and people ordering alcohol delivery directly to the beach.

- We all know the hysteria about critical race theory is not really about critical race theory.

- There was a "Redneck Rave" in Kentucky that ended with 30 criminal charges, someone's throat being cut, and another person getting impaled on a log.

--

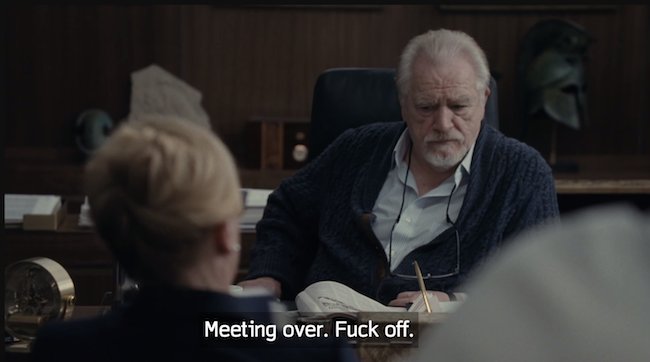

Watching

I know I am the last person to watch Succession, but I always thought it was going to be this intense drama like Mad Men or something but making all these super rich people looking cool and smart. But it is actually like Veep for super rich people. Or like a British satire of corporate America. It is so funny and everyone is stupid and awful just like real life.

--

Listening

New Slothrust song this might be a Crisis Palace record I think this is the third song featured by this band.

--

I endorse

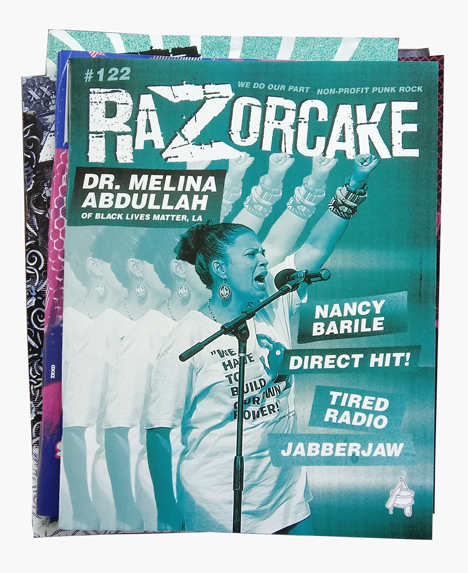

Razorcake. My friend Theresa introduced me to Razorcake, which is a Los Angeles-based zine dedicated to "DIY punk, independent culture, and amplifying unheard voices" and it is great. A lot of fun band interviews but interviews with all kinds of people like this month's cover feature is a founding member of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles for example. They are running a subscription drive for just a few more days so go subscribe 10 issues for $17 or you can even just donate go do it you love independent media you are obsessed with it.

--

Well this weekend I am getting a haircut and going to a Red Sox game so that will be a real big thing. And today I went to a coffee shop to do some work, another first. My longtime barista said welcome back oh by the way here's the wifi password it's not the same, and I said oh Joe, none of us are the same anymore are we, and we had a good laugh and then I sat down and wrote this for a few hours.

Jacoby is doing OK ups and downs but we are having to get increasingly creative to get him to take his pills because he keeps catching on and spitting them out. Jamie is like the Anthony Bourdain of getting dogs to take pills the other day she coated it in coconut oil and put it inside a piece of brie with sprinkles of venison on top. Michelin starred dog pills.

I like to think that this newsletter is much like a dog pill wrapped in brie and coconut oil, sprinkled with venison, irresistible to you but it also serves an important purpose. Please don't spit it out it took a long time to prepare.

Tate