81: Near enemies

Near enemies is a concept that I came across a few years back that I have found useful when thinking about climate change, but also just life in general. I can't even remember how I first heard the term, but it's actually a Buddhist idea that says for every desirable behavior or state of mind, there

Digging, burning, sucking up and burying, to perpetuate a system that was not working in the first place

Near enemies is a concept that I came across a few years back that I have found useful when thinking about climate change, but also just life in general. I can't even remember how I first heard the term, but it's actually a Buddhist idea that says for every desirable behavior or state of mind, there's a slightly different version of it that is actually harmful, but it's so similar that it's really hard to tell the two apart. We often think of conflicting forces as being polar opposites, like love and hate, for example. But we get into trouble more often when we are roped by concepts that disguise themselves as love, such as co-dependency.

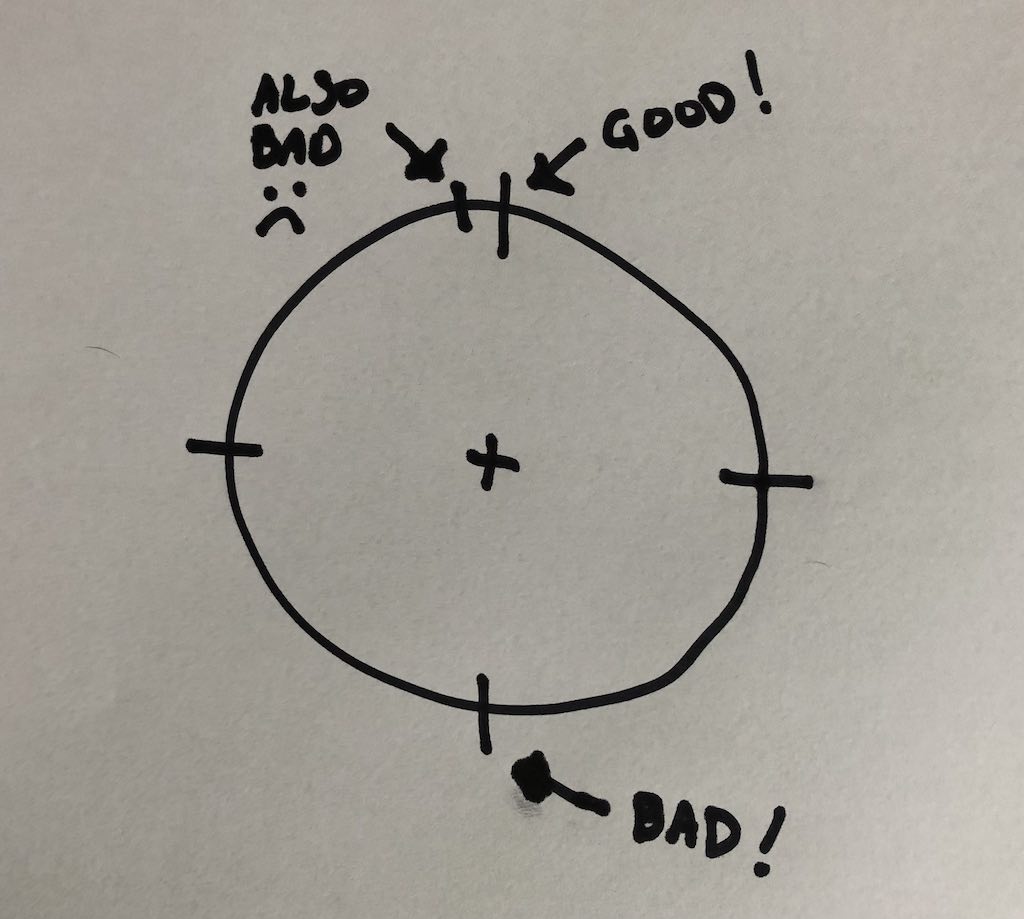

I'm sure you have experienced this phenomenon many times, where you see something and are like, wait a second I was pretty sure that was a good thing, but this version of it is actually really bad. It's tricky because as a result you can embrace the bad thing to your own detriment, but the near enemy also sows distrust in the good thing. Here is kind of how I envision of it, like if all the different things you could do in life were along a round dial:

I cannot believe how long it took me to make this shitty graphic this is copyrighted do not use without express permission.

I have mentioned this idea briefly in the newsletter before, but have been thinking about it a lot lately while reading a bunch of things about carbon dioxide removal (see last week's issue). Climate change is lousy with near enemies, and I feel like almost every useful action you might take could be moved just one notch along the dial and become malignant (carbon taxes comes to mind, depending on how the money is collected and spent). This makes it really hard to know what the right move is. One field where this is very much the case is carbon dioxide removal. Sometimes called negative emissions, or somewhat incorrectly, carbon capture, it is a powerful idea and, as such, open to dangerous near enemies.

I have been reading a lot about carbon dioxide removal because it's in the news lately, we've been running articles on it at the day job, and it's an area in climate change where I hold a lot of conflict and concern. So I've been trying to figure it out via google and reading several papers with beautiful arrays of colored charts and line graphs. And now for my own benefit and maybe or maybe not yours I'm not sure, I am going to attempt a concise summary of this topic along with some of my current thoughts about it seriously I am going to do this yes ok goddamnit here we go. I'll limit the charts and acronyms as much as possible.

What is carbon dioxide removal?

I feel like most people hear this term and think of giant industrial vacuums sucking pollution out of the sky, which is partially accurate, but that impression and all the fuzzy terminology makes this a confusing topic from the start. Carbon dioxide removal (I'm sorry but I am going to call it CDR), very simply, means removing CO2 from the atmosphere, using an array of methods, but there are two main categories.

One is enhancing natural processes that remove carbon from the atmosphere, often in the form of land use like planting trees or agricultural methods that hold more carbon in the soil. (This is sometimes called AFOLU ah jesus acronyms.) There are a lot of opinions about this subset alone, but they are not to be discounted; something like 25 of the 80 climate solutions identified by Project Drawdown involve land sinks and land management practices. The concept is deceptively simple—some carbon naturally lives in the air, some carbon naturally lives in the ground, and we have fucked that balance all up. We know how to do this already and there are lots of simultaneous benefits, but there are also big potential problems surrounding how it's deployed at large scale.

The other gets us into giant vacuum territory. These are chemical processes that extract CO2 right out of the air and turn it into something else we can use or just stash away somewhere. There are different forms of this too: the giant vacuums sucking carbon out of the sky are called direct air capture (DAC!), carbon capture and storage grabs the emissions at the source (CCS!), and then there's bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS!). BECCS is when you burn organic material (like corn or sugarcane or poops) for energy, and then capture the carbon it burns and put it, again, somewhere.

These technologies, especially BECCS, took the spotlight when one of the IPCC's big "we're fucked" reports relied heavily on BECCS in its pathways to meet carbon reduction goals, even though it was basically a hypothetical solution.

Is carbon dioxide removal at large scale necessary?

Maybe not, but probably, and if so it depends a lot on what you mean by carbon dioxide removal. I know that is evasive, but there are zillions of ways to answer this question.

I mentioned last week that it's becoming climate gospel that meeting CO2 reduction goals is flat out impossible without CDR. While that could be technically true depending on your definitions (and which climate scientists you ask), I think when put like that it's misleading and used for sometimes nefarious purposes. So to bring some clarity to that question, it is annoyingly necessary to parse some of those definitions.

For starters, there's the 2°C of global warming limit, which is the original IPCC goal that would lead to lots of very bad consequences, but not nearly as bad as say 3-point-something degrees we are on target for now. More than half of the scenarios IPCC identified to hit this target require different forms of CDR.

Then there's the 1.5°C goal, which was identified in another "we're fucked" report from the IPCC, which said, actually 2°C is looking so bad we should really be shooting for 1.5°C, but also, it's almost too late to do that. In that report, all of the scenarios the IPCC (which is really a mishmash of tons of researchers and their individual work) required CDR to hit the goal.

BUT, since then, different teams of researchers have in fact identified pathways to 1.5°C that either greatly reduce the reliance on CDR, or do not rely on it at all. As you can imagine, these are heavy lifts, but really, they are all kind of heavy lifts at this point, and depending on who you ask, 1.5°C may not even be a possibility anymore. The other important qualifier is that within the scenarios that do require a bunch of CDR, there are some that entirely or almost entirely rely on land use, soil, reforestation etc. Here's one of the few graphs I will rely on (I didn't make this one, the IPCC did).

So yeah, you can see that P1 is looking pretty sharp there, I see you P1 respect. But P4 over there? Boooo. Burn burn burn and suck suck suck. I also love the term "greenhouse gas intensive lifestyle," like please respect my greenhouse gas intensive lifestyle.

One thing to note that will come into play later is that a hallmark of the pathways that get by with just forests, soils, agriculture, etc., is that they require very stringent emissions reductions starting pretty much yesterday, and they rely heavily on the reduction of energy demand, so shrinking the energy economy. They do, however, increase quality of life in both the Global North and Global South, and scenarios that support Sustainable Development Goals rely far less on carbon dioxide removal technologies. BECCS, on the other hand, has all sorts of dicey and uncertain side effects.

Why don't we just do the good stuff?

So why don't we just stick with P1 and call it a day?

For one, P1 is really hard! But there are several reasons to be concerned that if we don't put greater focus on CDR we are going to be in trouble. One has to do with our carbon budget, which refers to the fact that there is a finite amount of CO2 we can burn before we are on a runaway train past 1.5 or even 2 degrees. And we've already burned almost all of it. (In fact, there's a chance we have already exceeded it.)

Once we overshoot by certain amount, removing many billions of tons of emissions from the atmosphere becomes the only way back. Something I'm just not sure about and am more than a little worried about is whether we have crossed into territory where the mostly land use change and low-energy demand scenarios are not enough. I don't know.

Another problem is that there are certain things we rely on, like some industrial processes and air travel, for example, that we don't know how to do yet without burning carbon. Ratcheting up CDR could give us time to figure it out.

These arguments, and others, form the case for pouring more money and attention into carbon dioxide removal as a form of harm reduction—a way to curb damage during the energy transition. And I'm sure that actually understates the enthusiasm a lot of people have for CDR as they imagine the potential of its aggressive use in combination with other aggressive mitigation measures.

Carbon dioxide removal as the mother of all near enemies

So that's my kind of measured summary of what I know on the topic, which to be totally honest, is still a work in progress. I have read a fair amount about it at this point, but am open to counterpoints or other research papers that I need to cram into my brainpiece, etc., and of course, what we know is always changing.

But this is where we get to the Crisis Palace part, wherein I am fairly terrified of what a big push for carbon dioxide removal could unleash, while operating undercover as a near enemy of both harm reduction and emissions reductions.

What I mean by that is, whenever someone is making the case for climate fixes that do not at their core stop the burning of fossil fuels or end the extractive energy economy, their reasoning sounds quite similar to all other climate change advocacy, sometimes even climate justice advocacy. They outline short-term reduction of X gigatons of carbon in the atmosphere, public health benefits, how it will prevent harm to vulnerable communities, improve quality of life. In fact, they often say exactly the kind of thing I would say, but then the finale is something like, "and that is why we need to switch to natural gas drilling" or "and that is why need to deploy direct air capture plants at scale."

And I honestly give most of those people the benefit of the doubt that they do want similar outcomes as I do. The problem is, while certain benefits make these strategies appear to be solutions, they can actually work in favor of the underlying problem, or merely replicate the underlying problem in different venues. The climate justice community calls them "false solutions" which is way better messaging than near enemies, but I'm going to stick with my thingy. They look like solutions. But they are one notch over on the dial such that they become a harmful force.

A big part of the problem is that they do a lot of heavy lifting for the actual tried and true enemies on the opposite side of the dial.

Case in point: A recent study from MIT concluded that “Our projections show that CCS can play a major role in the second half of this century in mitigating carbon emissions in the power sector. But in order for CCS to be well-positioned to provide stable and reliable power during that time frame, research and development will need to be scaled up.”

This study was funded by none other than ExxonMobil. To be fair, ExxonMobil are experts on climate change because after all they did know it was coming since the 1970s and spent millions to block action to prevent it. Then again, it would probably be best for everyone if ExxonMobil and every other fossil fuel company gathered up all of their little opinions and ideas on how to stop climate change, put them all in their little backpacks, zipped them up real tight, and then fucked right off forever.

To further elaborate on what ExxonMobil envisions as a climate solution, as noted last week, citing an article in Politico:

Exxon and other oil producers are embracing carbon capture as a technology that will enable their oil and gas businesses to continue to operate in a carbon-constrained environment … Exxon, unlike European rivals like Shell and BP, has not vowed to transition away from fossil fuels, arguing that oil and gas will remain key to the global economy for decades as building blocks for plastics and to drive global expansion of electricity. Instead, the company plans to devote its attention to capturing and storing the carbon emitted from oil and gas — and capitalizing on the massive new business opportunity.

Even if well-intentioned champions of CDR technology do not share this vision of the future, they are pushing in the same direction. That direction is toward P4 up there, on steroids. Dig, burn, suck, bury, repeat. Build an entire second fossil fuel industry perched atop the first one to ensure we can continue our greenhouse gas intensive lifestyles.

Proponents would argue that they can make sure that doesn't happen. Maybe they can build just a little bit of direct air capture or BECCS as a treat to get us back on the right track. Or if and only if fossil burning is slashed at the same time. Yes, we obviously need to reduce emissions too, they argue. If that is the plan, it demonstrates far more confidence than I have in the ability of a profit-seeking industry to operate with restraint.

When fracking was being sold by many in the environmental community as a climate solution, the pitch was that it was just a bridge fuel to get us on the right track. Yes there were concerns about methane leaks, but we could manage them. Fast-forward to now, and industry has locked in sprawling new fossil fuel infrastructure, produced a glut of natural gas in the market, poisoned water supplies in rural communities, and spewed methane—which is short-lived but eight times as potent a contributor to global warming as CO2—to all time high levels in the atmosphere. Cool bridge bro!

These same kinds of threats stand to follow a booming carbon removal industry, as "pipelines need to be built, vast geological reservoirs deep underground need to be fashioned into carbon dioxide storage facilities, costly new technologies for vacuuming carbon from the air and factories need to be brought up to scale."

Some of these practices require enormous amounts of energy, water, and chemical absorbents. Where would these plants be located? Where would those new pipelines and underground reservoirs be built to move and store all that liquid carbon? I think we all know the answer is on Tribal land, in poor rural areas, in communities of color. This is why environmental justice advocates typically oppose carbon removal as a climate solution. They know who will pay the price as that second fossil fuel industry is built.

What is the problem we are trying to solve?

So I guess my conclusion for now is, deeply concerned about chemical carbon capture, hopeful for land use solutions, and generally just worried that we're past the time when we can reject even our shittiest solutions. But I don't mean for this to be an anti-technology screed, either. Remember the AFOLU solutions, the agriculture and soils and reforestation that I like so much more? Those have near enemies too! Land use can become a euphemism for land theft. Planting trees, a license for business as usual in all other regards. Land management as a form of carbon reduction keeps getting exposed as a hustle that uses flawed or funny math to justify doing nothing at all. Also, forests burn.

The bigger point is that we are entering a period of climate action where the right steps and the wrong steps are going to be increasingly difficult to tell from each other, because we are exiting the period in which the right steps meant doing absolutely anything and the wrong steps meant moving backwards. Everything that needs to be done now is difficult, politically, technologically, economically, personally. What's easier, rapidly ending the fossil fuel industry, or rapidly building a second one?

That means the solutions we choose are based on the best science we have, but also on our values. What we are willing to sacrifice, what control we are willing to give up, and what we believe is possible in terms of humanity's ability to change.

I recently watched a panel on police reform versus abolition, and someone from the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights defended radicalism by defining it as action that addresses the root of the problem. That feels like a useful framing in separating solutions from their near enemies. Our values are largely determined by what we believe the actual problem of climate change is.

If we view it not as the state of the planet's atmosphere, but as the extracting and burning of fossil fuels for energy, we wouldn't build new infrastructure that allows fossil fuels to burn. If we view the problem as an economy that runs on extraction and exploitation, maybe that helps us navigate difficult technology and land use decisions. Otherwise we run the risk of building a planet covered in more and more industrial plants, allowing us to keep digging, burning, sucking up and burying, all to perpetuate a system that was not working well for most of us in the first place.

--

Watching

My personal film festival in which I catch up on movies I've been wanting to see continues, and the latest winner (there have been losers, don't ask about X-Men Apocalypse) is Another Round, a delightful and sad and sweet and funny Danish film starring Hannibal himself Mads Mikkelsen. I believe the tagline mentions that it is "life-affirming," and I can affirm that is the case. Just watch it you don't have to read what it's about first it will be better that way. It's on Hulu.

This movie is a comedy

--

Listening

Suss, High Line

--

OK I'm going to wrap up because this was kind of a long and gnarly one, no links today it's getting late but I will have all of the links you hunger for next week don't worry. I will give you one good link, because I think it's important to know whether or not you are cheugy, and adjust accordingly.

This was also the first issue in the new format, which now lives at crisispalace.com so that's fun. I'm still polishing up the new site and figuring out the mail plugin and I have to migrate over the archives, but we will get there and I think it will be an improvement. Don't you love that feeling when you move into a new palace, getting all our stuff set up, hanging up the art. See you next week roomies.

Tate

PS I don't think there will be a like/heart function now, so what you're going to have to do is just respond and in the text of the email say "heart" or "like" or maybe "good one" and that will do the trick.