37: Shouting from the rooftops

When people show up, you don’t have to compromise

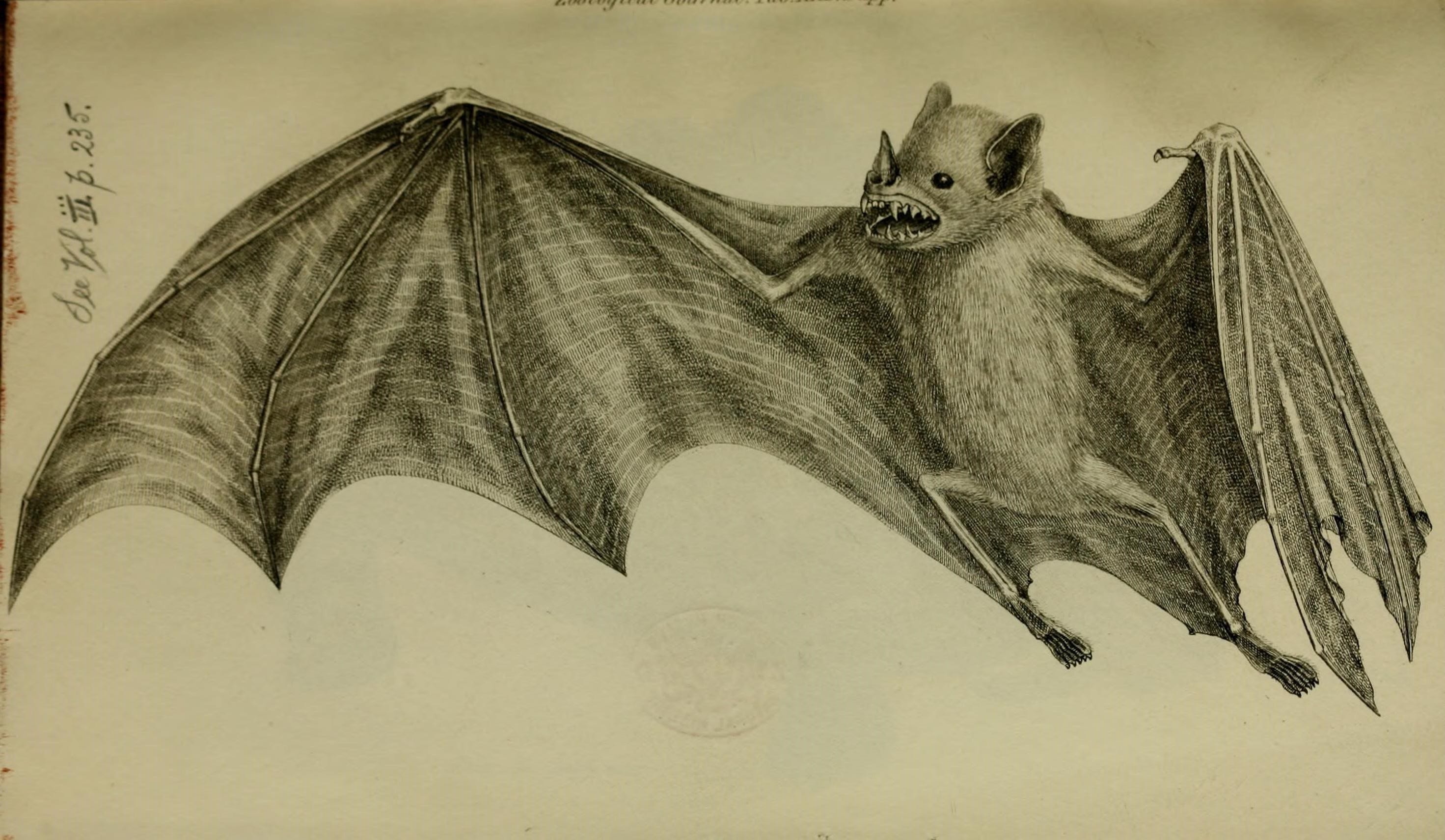

The Zoological journal. London: W. Phillips, 1824

If you know the name Erica Chenoweth, it’s probably in relation to the Harvard professor’s widely cited “3.5% rule,” which poses that no government can withstand a challenge from 3.5% or more of its population without accommodating it or in extreme cases falling to it. This is an alluring figure, and one that has been embraced by climate activists among many others. So has research by Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan that found nonviolent resistance campaigns were twice as likely to achieve success as violent campaigns.

That last conclusion comes from their book Why Civil Resistance Works, which I finished earlier this year just as we started to really get into the shit so I didn’t talk about it much at the time. But it’s a pretty remarkable book and I’ve mentioned it here and there but figured I would revisit it now because reviewing a seven year old book two months after I finished it is a solid CP move.

The top line conclusions from the book are important—studying over a century of resistance campaigns the authors found that sometimes nonviolence works, sometimes violence works, but nonviolence works way more often. One big reason is that it’s easier to get to that critical % of participation when you don’t have to recruit people to commit violent acts. Another big finding is that nonviolent campaigns more often result in democratic, stable outcomes.

So that’s really something, but my favorite parts of the book were its case studies of resistance campaigns that succeeded, failed, or partially succeeded and partially failed, and what we can learn from them. So even more useful than the conclusion of “nonviolent campaigns of a certain size succeed” are the details of how different movements reach that threshold, and why sometimes they fail anyway. For example, one critical quality other than sheer size is diversity of participants and tactics. Successful movements are non-monolithic.

The most interesting of the case studies is probably the 1979 Iranian Revolution. This is obviously a big, complicated story, but one of the main factors Chenoweth cites in the success of this revolution is that there was a huge diversity of participants, which made it bigger and more varied in its tactics, and more difficult for the regime to repress. The obvious faction involved was the powerful religious leaders who ultimately seized control in the aftermath and ended up forming another violent, oppressive government. For that reason, the revolution is sometimes characterized as a failure.

But the movement itself was overwhelmingly nonviolent in its tactics and involved pretty much every segment of society, succeeding in toppling a repressive monarchy where previous violent uprisings had failed. Participants included student activists, workers, professionals, merchants, academics, you name it. There were mass protests in the streets, but there were also nightly poetry readings. In fact, the majority of the people who participated in the revolution never actually clashed with the regime. One hallmark was people staying home and shouting anti-Shah slogans from their rooftops at night. It was a movement where anybody could do something.

In contrast, there was an armed guerrilla movement happening at the same time, but the authors point out that it was unable to to gain significant participation. In part because it was violent, but also because of its rigid Marxist litmus test that the coalition-based movement did not have.

One of the most interesting things about this diversity of participation is that, while you might expect that kind of big tent approach would lead to compromise or capitulation, in some ways it did the opposite. Toward the end of the revolution, the Shah offered steps toward liberal reform that opposition would have jumped at in earlier days. But by that time, there was only one acceptable outcome—regime change. In other words, when people show up, you don’t have to compromise.

Of course, the shadow of this particular nonviolent resistance is its violent aftermath, what Chenoweth and Stephan call an anomaly in their conclusion that nonviolent campaigns more often lead to peaceful results. For a bunch of reasons, radical clerics ended up having too much power within the coalition and locked everyone else out. The authors pose a couple of explanations for this. First, while its uncompromising goal was to remove the Shah, different factions sought different things and the movement never coalesced around a shared vision of a post-Shah Iran. They also suggest that the secular leftist guerrilla movement provided an excuse for the religious regime to stamp out other secular voices.

So there seem to be two potential dangers here, one being a movement perhaps too ecumenical to form a shared vision. Another in the way that one faction isolating itself by being too rigid in both politics and tactics can be destructive, even setting aside the moral question of resorting to violence.

But for me, the biggest takeaway is just how important it is for campaigns to make it easy for anyone to participate, on some level. You need the people who are the most dedicated, with the savviest politics, who are sacrificing the most, but if that’s all you have, you won’t get to that unstoppable critical mass. Activists tend to emphasize certain kinds of hard or risky work, but different people will have different things to offer a successful movement. That includes the people sitting in and getting arrested and the people just shouting from rooftops to signal their approval. In the contemporary pro-choice movement in Argentina, for example, the performative symbol of just wearing the color green has become a source of real power.

There is this anecdote from another book I have talked about before, Towards Collective Liberation, which makes a related observation in a case study of the Rural Organizing Project in Oregon, which does working-class organizing around immigrant rights through a series of “living room conversations.”

While we want everyone to be an active leader in the struggle for racial justice, we know that is not going to happen immediately. Think of our work as concentric circles. The first circle is ROP board members and staff. The second circle is the leadership of local groups. The third circle is the membership of local groups. The final circle is the broader community that our local groups operate in. When we have a Living Room Conversation, we are essentially taking a slice of this pie with representation from each of these circles. While we would love to have everyone join as a member of the [Immigration Fairness Network], at a minimum we want everyone in the room to not join the Minutemen.

Links

- A third of the US population could end up experiencing one or more extreme weather events annually, including fun things like “flash drought” and quick-forming extreme thunderstorms.

- If the US had started social distancing one week earlier we could have saved 36,000 lives, one model of the disease found. Two weeks earlier and 83% of deaths could have been avoided.

- The patchwork nature of the country’s response—and of our social safety net—will make the coronavirus difficult to get under control because instead of a clear peak and decline it’s just going to go up and down all over the place and nobody will agree on what to do.

- Hundreds of workers in Massachusetts have filed complaints with OSHA about unsafe working conditions during the pandemic and OSHA doesn’t seem to give much of a shit.

- The opening Listerine anecdote from this Jason Isbell profile alone is a must read.

- A Quality Inn in Revere has been turned into a quarantine hotel for patients with coronavirus who can’t stay at home.

- Death Angel’s drummer said his COVID-19 coma was like being in hell tortured by Satan. “I’m still going to listen to satanic metal [but] I don’t think Satan’s quite as cool as I used to.” Not going to lie folks this is probably the one to click this week.

This is a headline I saw. Strange times.

Watching

I’ve been watching HBO’s The Leftovers which is a show all about grief and Justin Theroux’s chiseled torso. I never see that guy working out in the show though he is mostly hallucinating or punching walls but I guess that burns calories. I am 50% through the series and I like it. It has this sort of slow, relentless sadness and randomness to it that feels a lot like life can sometimes. I will say that unlike Lindelof’s Watchmen, there is still a little Lost stink on this show, like it’s meant to be an ABC primetime drama but they threw a Max Richter score behind it and slapped it up on prestige cable. Anyway, another glowing review from me, but it’s a good show really four stars check it out.

This is me discussing my summer plans.

Reading

I recently finished Sloane Crosley’s Look Alive Out There and she is very funny and insightful and it was also nice to read little stories about non-quarantine life. One standout essay is about when she unwittingly tried to climb one of the most treacherous mountains in Ecuador without any preparation whatsoever.

The constant state of newness in a foreign country lends a little drama to everything. Even the maiden operation of a local ATM demands problem-solving. It becomes increasingly difficult to parse personal adventure from objective adventure, until you’re certain everything should be a challenge, every path a learning curve. It is only later that someone native to the region hears you decided to ride a bicycle to the airport, laughs, and says: Not that steep of a curve.

Listening

New Jason Isbell.

Some of the things that we have ordered online include a lot of books, some fancy glassware because if you have to drink at home it might as well be classy. And the biggest item is a credenza, a piece of furniture we have desperately needed for the office for like four years but never wanted to buy.

It arrived on Tuesday unassembled in a 160 pound box for which the delivery guy was like I know I am essential but come on screw you guys. The box was on our porch all day because it was too heavy to move and we had nowhere to put it until the night when I hacked the giant thing open with a knife and brought it in piece by piece like the goddamn London Bridge. Wikipedia tells me it took over three years to put the London Bridge back together in Lake Havasu City and that is how long it will take me to put together this credenza.

Have a nice weekend everyone. Get some sun but jesus do not touch anything.

Tate